Johns Hopkins University (JHU) continues to pad its space community résumé with their interactive map, “The map of the observable Universe”, that takes viewers on a 13.7-billion-year-old tour of the cosmos from the present to the moments after the Big Bang. While JHU is responsible for creating the site, additional contributions were made by NASA, the European Space Agency, the National Science Foundation, and the Sloan Foundation.

One of the most pressing questions in astronomy concerns black holes. We know that massive stars that explode as supernovae can leave stellar mass black holes as remnants. And astrophysicists understand that process. But what about the supermassive black holes (SMBHs) like Sagittarius A-star (Sgr A*,) at the heart of the Milky Way?

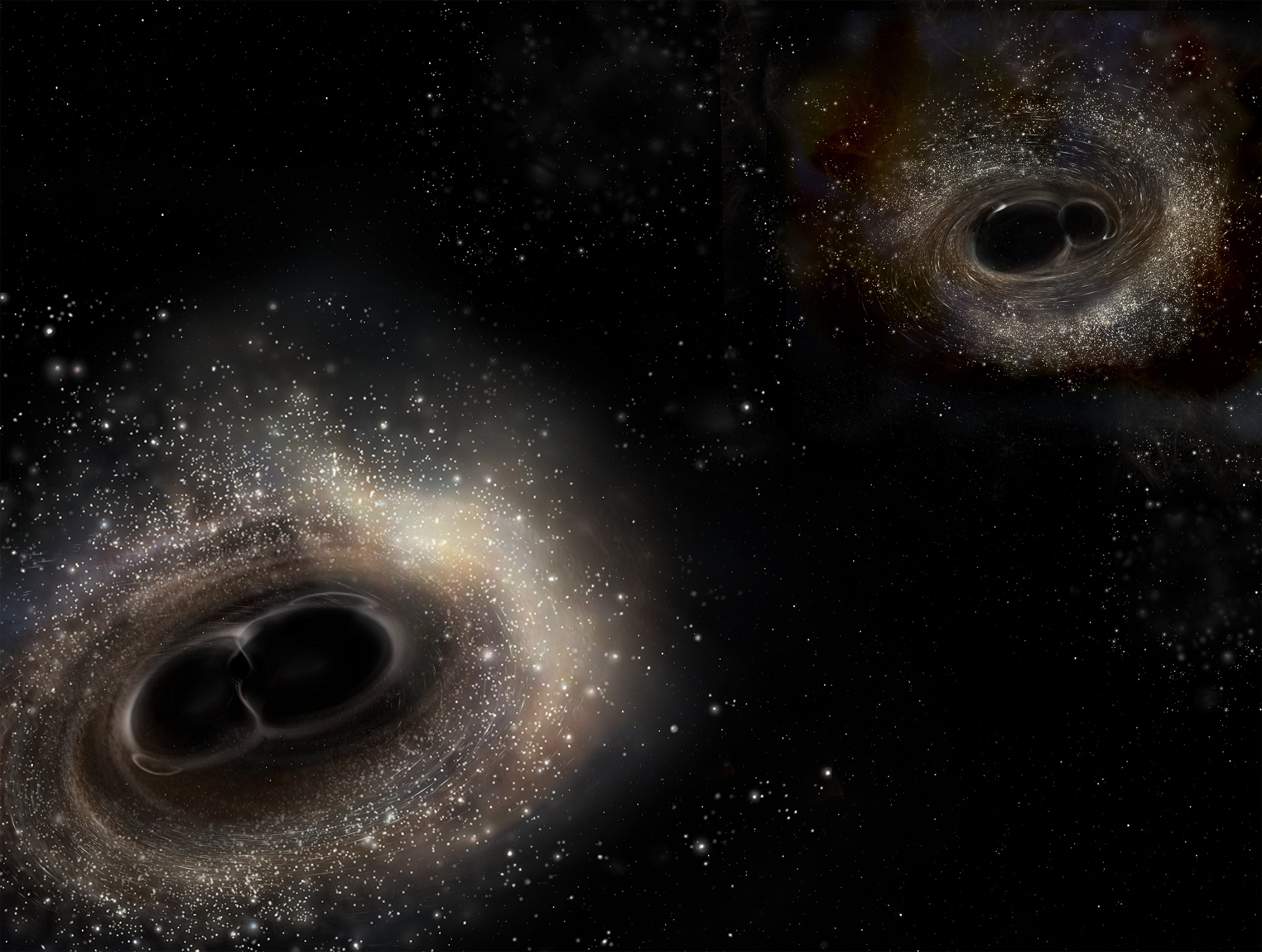

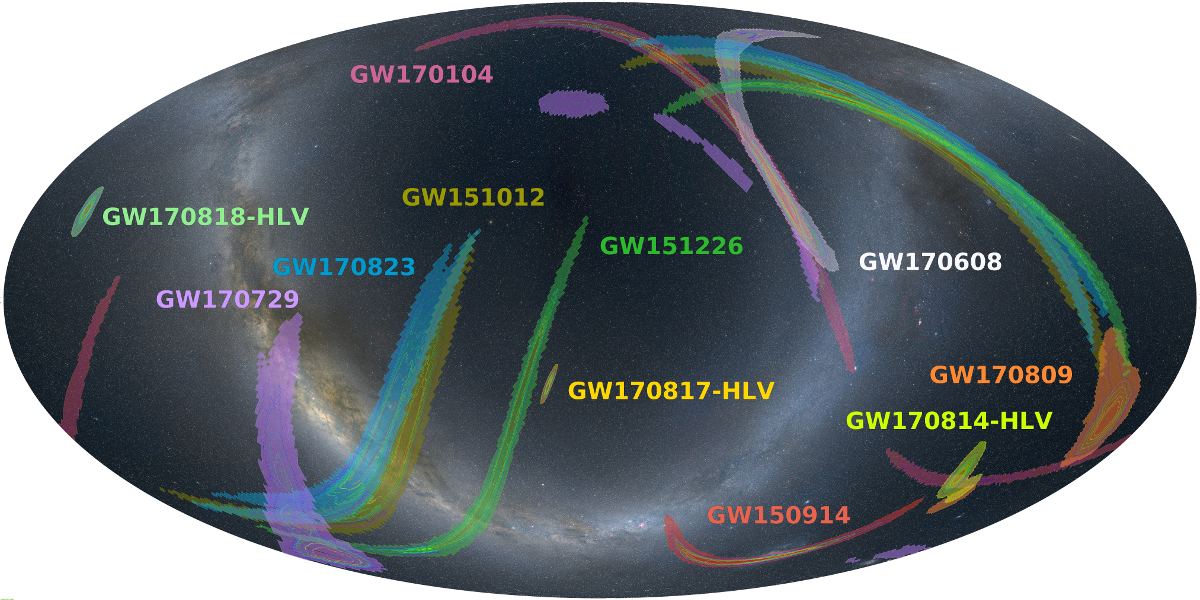

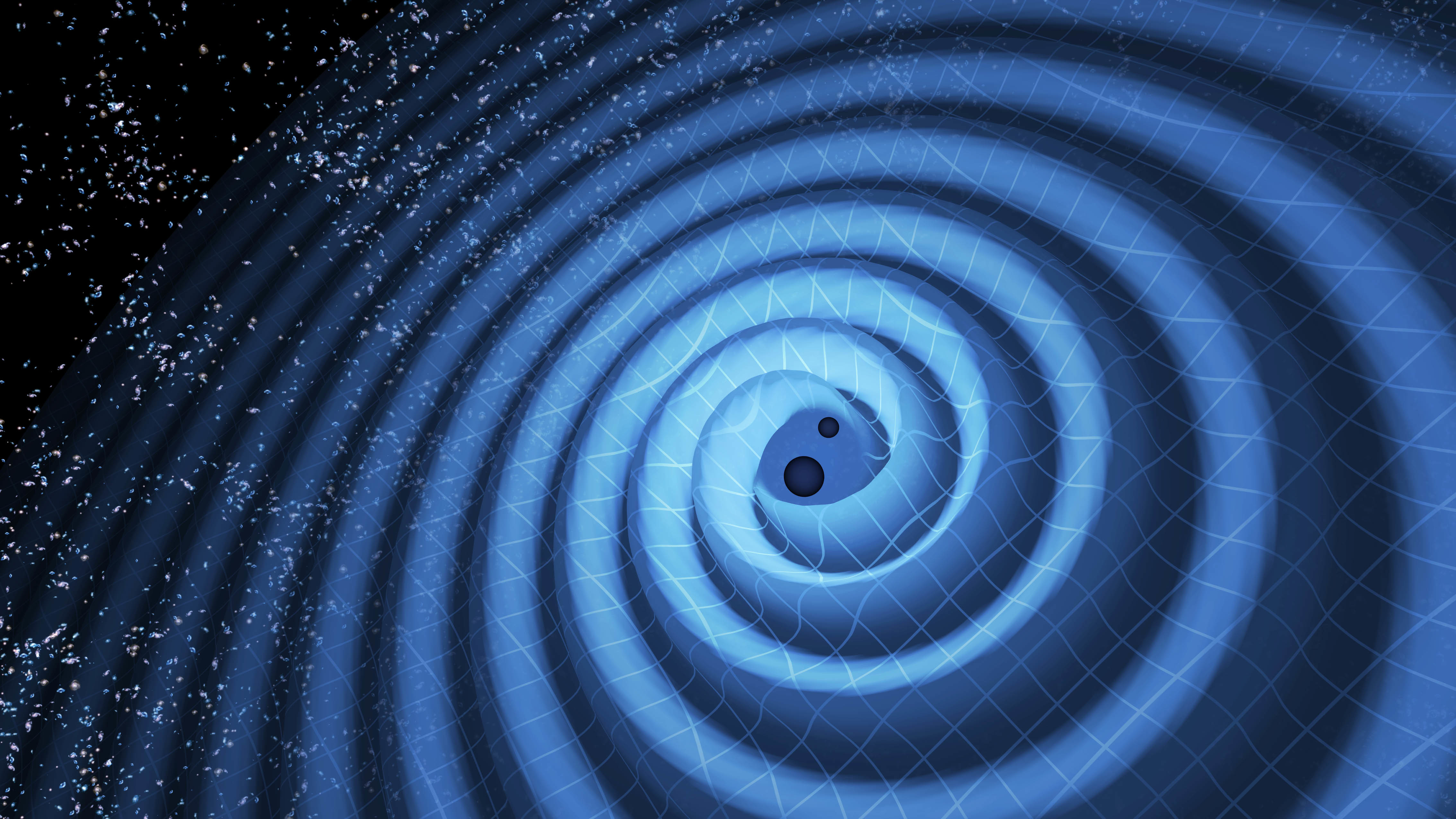

In February of 2016, scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) announced the first-ever detection of gravitational waves (GWs). Since then, multiple events have been detected, providing insight into a cosmic phenomena that was predicted over a century ago by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity. Artist’s impression of merging binary black holes. In February 2016, LIGO detected gravity waves for the first time. As this artist’s illustration depicts, the gravitational waves were created by merging black holes. The third detection just announced was also created when two black holes merged. Credit: LIGO/A. Simonnet.

A new simulation of black hole growth shows the different ways that they grow in different scenarios. In the nearby Universe, small black holes grow by accretion, while large ones grow via mergers. In the distant Universe, the reverse is true: small one grow via mergers, while large ones grow through accretion. Image Credit: Credit: M. Weiss

Illustration of the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, surrounded by its rotating accretion disk. Credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF

We talk about stellar mass and supermassive black holes. What are the limits? How massive can these things get? RSS: Sign up to my weekly email newsletter: Support us at:Support us at: Follow us on Tumblr: : More stories at Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Like us on Facebook: Instagram - Team: Fraser Cain - @fcain / frasercain@gmail.com /Karla Thompson - @karlaii Chad Weber - Chloe Cain - Instagram: @chloegwen2001 Music: Left Spine Down - “X-Ray”

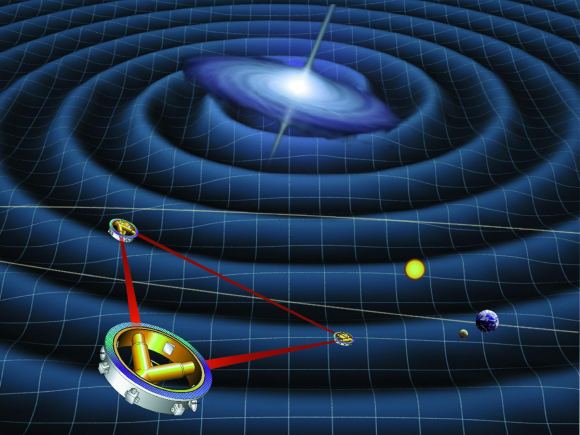

An illustration of the ESA’s LISA spacecraft, designed to detect gravitational waves from black hole mergers and other events. Image Credit: By NASA – NASA, Public Domain, (wikipedia.org)

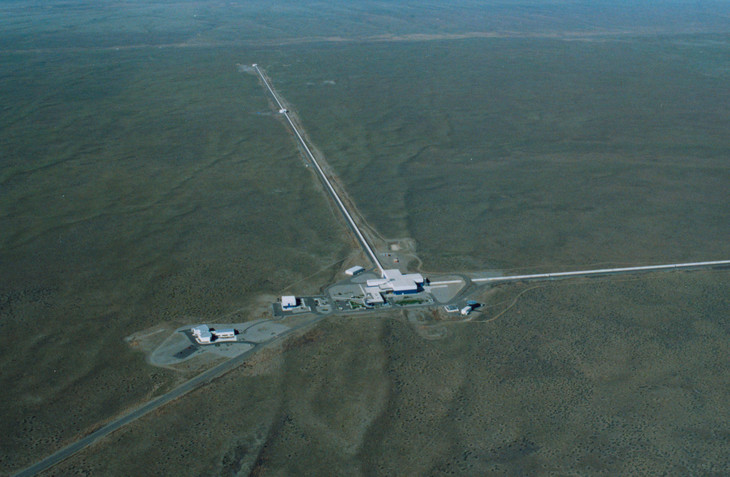

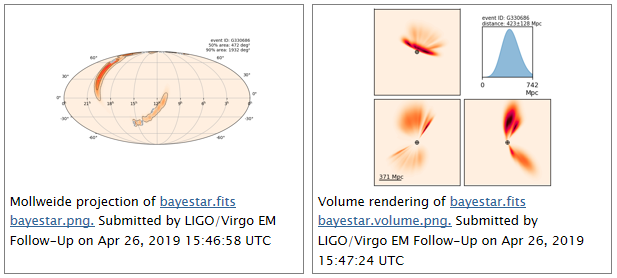

Aerial photograph of the LIGO detector site, located near Hanford in eastern Washington. Credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab

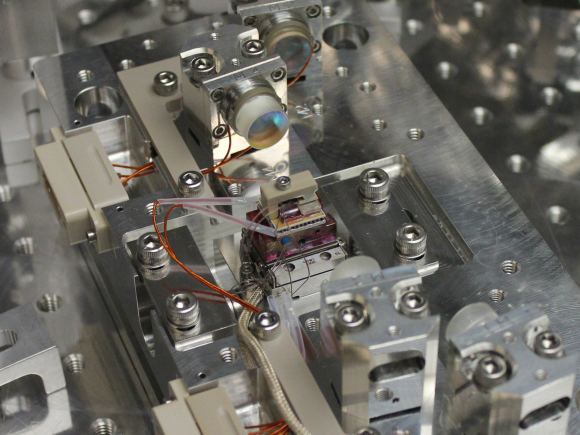

Detector engineers install hardware upgrades inside the vacuum system of the detector at LIGO Hanford Observatory in preparation for Advanced LIGO’s third observing run. Credit: LIGO/Caltech/MIT/Jeff Kissel

A new signal detected by LIGO/Virgo may be the so-called ‘holy grail’ of astrophysics: the merger of a neutron star and a black hole. They’ve discovered pairs of black holes merging, and pairs of neutron stars merging, but until now, not a neutron star-black hole pair.

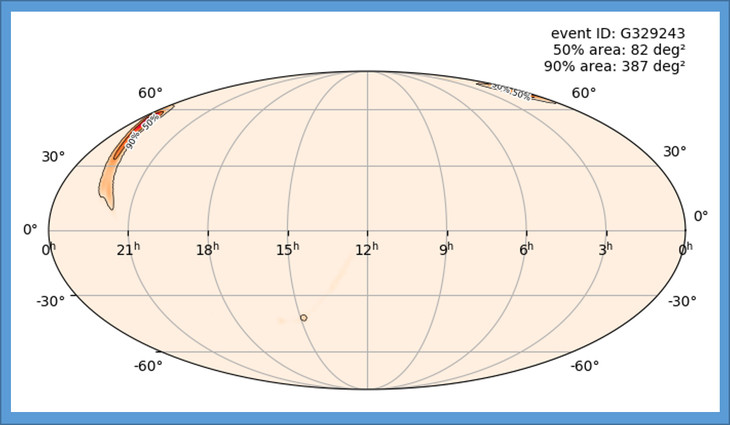

The region of sky believed to contain the source of the gravitational wave detected on April 8th, 2019. Credit: LIGO/Caltech/MIT

Some of the visual data from #S190426c that is generating so much excitement. Image Credit: LIGO/GraceDb.

Audio Podcast version: ITunes: RSS: Sign up to my weekly email newsletter: Support us at:Support us at: Follow us on Tumblr: : More stories at Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Like us on Facebook: Instagram - Team: Fraser Cain - @fcain / frasercain@gmail.com /Karla Thompson - @karlaii Chad Weber - Chloe Cain - Instagram: @chloegwen2001 Music: Left Spine Down - “X-Ray” References: Ligo_signals LIGO Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory Supported by the National Science Foundation Operated by Caltech and MIT Detction Lio News Geo 600 Record Squezing> Ligo News Nasa Archive Gravitational Events Twitter

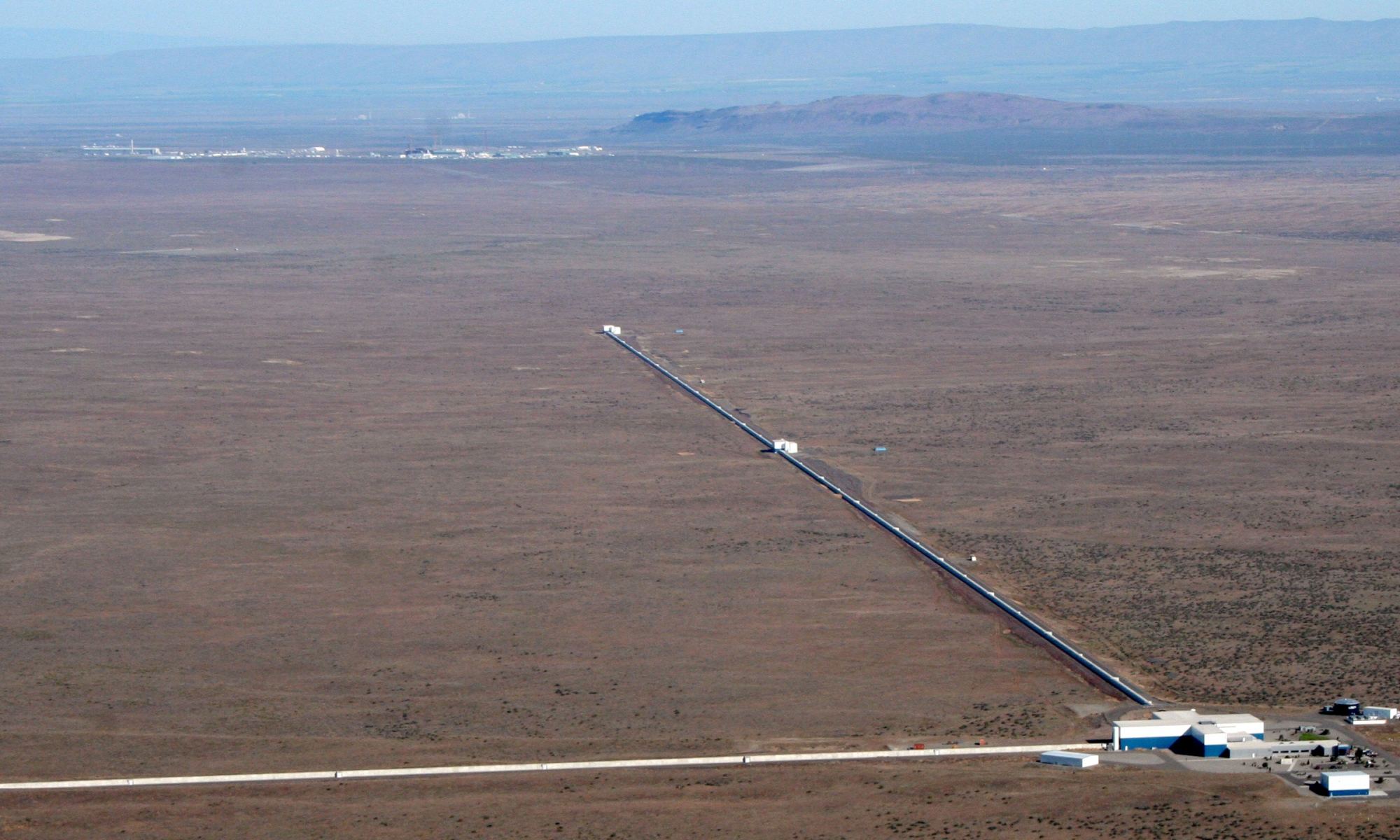

When two black holes merge, they release a tremendous amount of energy. When LIGO detected the first black hole merger in 2015, we found that three solar masses worth of energy was released as gravitational waves. But gravitational waves don’t interact strongly with matter. The effects of gravitational waves are so small that you’d need to be extremely close to a merger to feel them. So how can we possibly observe the gravitational waves of merging black holes across millions of light-years?

Schematic showing how LIGO works. Credit: Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

LIGO mirrors being upgraded. Credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory is made up of two detectors, this one in Livingston, La., and one near Hanford, Wash. The detectors use giant arms in the shape of an "L" to measure tiny ripples in the fabric of the universe. Credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab

What does it feel like to be part of a history making discovery? The thrill of detecting the first gravitational waves, which originated from the collision of two black holes, is still front of mind for many at The Australian National University (ANU) Centre for Gravitational Astrophysics. “It was just so exciting. I had been working on this project for 20 years and, finally, it happened!” Distinguished Professor Susan Scott Researchers at ANU played a pivotal role in this discovery by providing key instrumentation, including steering mirrors and stabilisation systems, to the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO). Learn more at the Australian National University #science #stem MUSIC:

Artist’s impression of merging binary black holes. Credit: LIGO/A. Simonnet.

An explanation of the LIGO detectors. Credit: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

The first stars to appear in the universe are no longer with us – they died long ago. But when they died they released torrents of gravitational waves, which might still be detectable as a faint hum in the background vibrations of the cosmos.

Follow all the show updates at Full podcast episodes: Support: Were the dark ages really dark? What is a perturbation, and how did they grow in the early universe? When the first stars awoke, what happened? I discuss these questions and more in today’s Ask a Spaceman! Follow: on twitter Follow:on Facebook Watch on YouTube: Go on an adventure: Keep those questions about space, science, astronomy, astrophysics, physics, and cosmology coming to #AskASpaceman for COMPLETE KNOWLEDGE OF TIME AND SPACE! Big thanks to my top Patreon supporters this month: Robert R., Justin G., Matthew K., Kevin O., Chris C., Helge B., Tim R., Steve P., Lars H., Khaled T., Chris L., John F., Craig B., Mark R., David B., Stephen M., Andrew P., and George L.! Music by Jason Grady and Nick Bain. Thanks to WCBE Radio for hosting the recording session, Greg Mobius for producing, and Cathy Rinella for editing. Hosted by Paul M. Sutter, astrophysicist at The Ohio State University, Chief Scientist at COSI Science Center, and the one and only Agent to the Stars License Creative Commons Attribution license (reuse allowed)

A close up of LIGO’s quantum squeezer. Credit: Maggie Tse

Animation showing a squeezed state of light. Credit: Wikipedia user Geek3

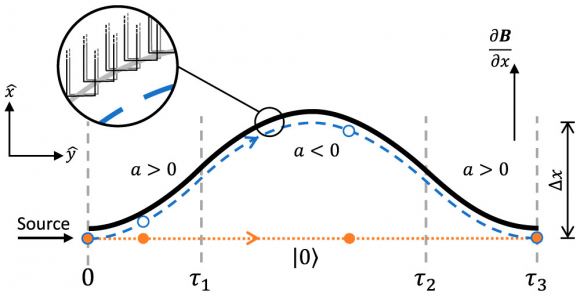

Perhaps the most surprising prediction of general relativity is that of gravitational waves. Ripples in space and time that spread through the universe at the speed of light. Gravitational waves are so faint that for decades their detection was thought impossible. Even today, it takes an array of laser interferometers several kilometers long to see their effect. But what if we could detect them with a table-top experiment in a university lab?

The superposition would be shifted by gravitational waves. Credit: Marshman, Ryan James, et al

Gravity might be caused by quantum interactions. Credit: SLAC National Accelerator Lab

Map of current and planned gravitational wave observatories. Credit: Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab

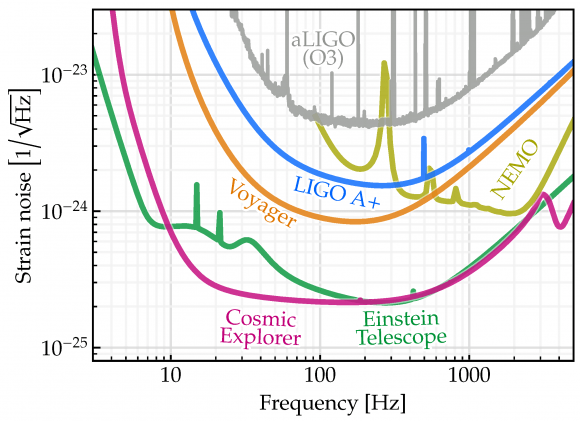

Sensitivity of Cosmic Explorer and current observatories. Credit: Evan D. Hall