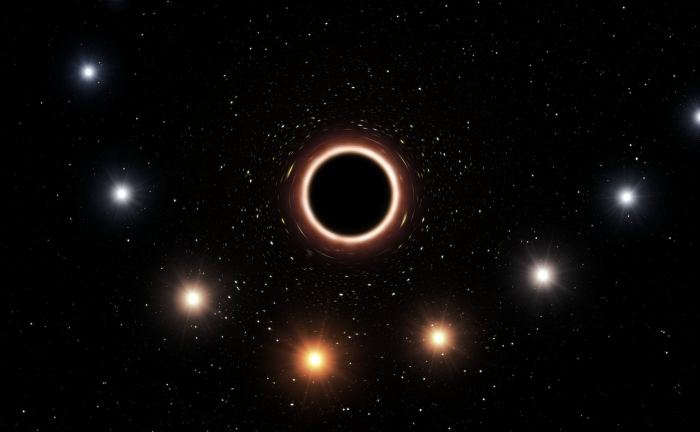

Artist’s impression of the path of the star S2 as it passes very close to the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

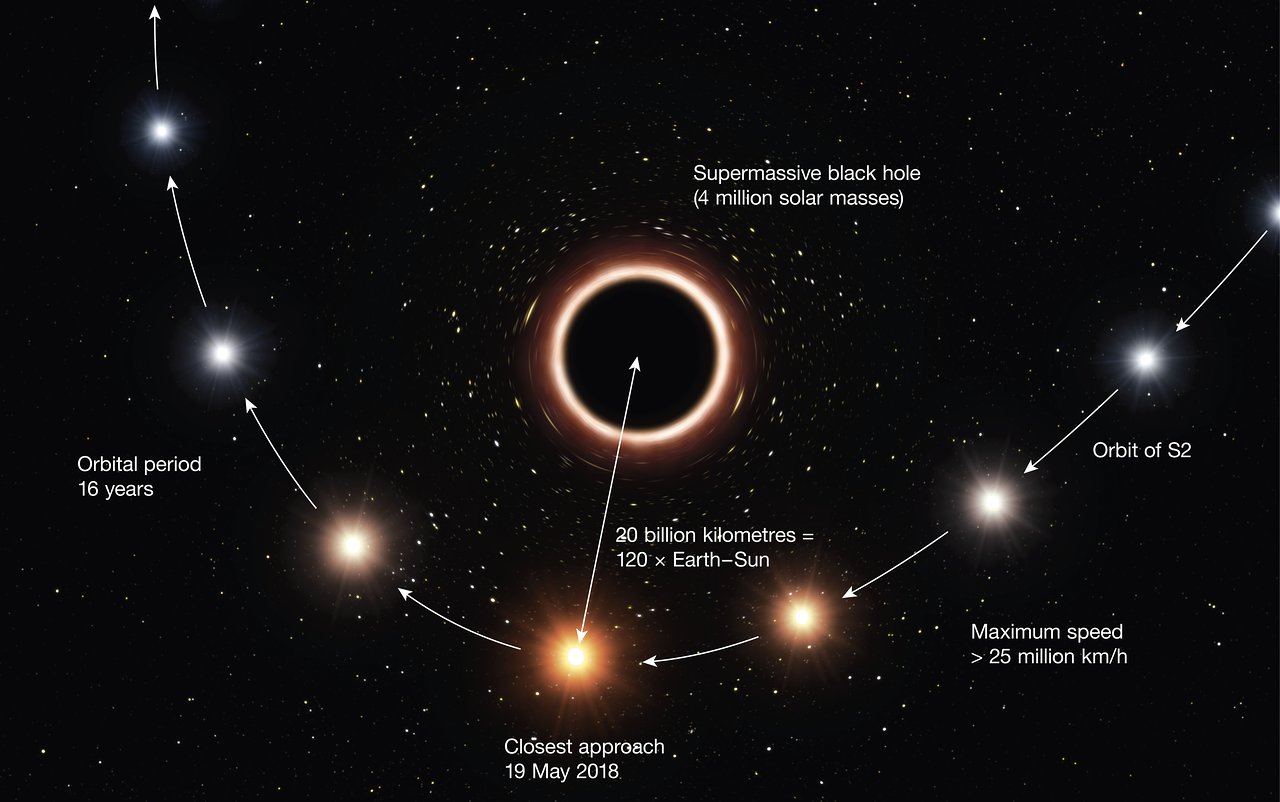

Annotated image of the path of the star S2 as it passes very close to the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

This artist’s impression video shows the path of the star S2 as it passes very close to the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. As it gets close to the black hole the very strong gravitational field causes the colour of the star to shift slightly to the red, an effect of Einstein’s general thery of relativity. In this graphic the colour effect, speed and size of the objects have been exaggerated for clarity. More information and download options: Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser Category Science & Technology License Creative Commons Attribution license (reuse allowed)

This zoom video sequence starts with a broad view of the Milky Way. We then dive into the dusty central region to take a much closer look. There lurks a 4-million solar mass black hole, surrounded by a swarm of stars orbiting rapidly. We first see the stars in motion, thanks to 26 years of data from ESO's telescopes. We then see an even closer view of one of the stars, known as S2, passing very close to the black hole in May 2018. The final part shows a simulation of the motions of the stars. More information and download options: Credit: ESO/GRAVITY Collaboration Category Science & Technology License Creative Commons Attribution license (reuse allowed)

At the center of our galaxy, roughly 26,000 light-years from Earth, is the Supermassive Black Hole (SMBH) known as Sagittarius A*. The powerful gravity of this object and the dense cluster of stars around it provide astronomers with a unique environment for testing physics under the most extreme conditions. In particular, it offers them a chance to test Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity (GR).

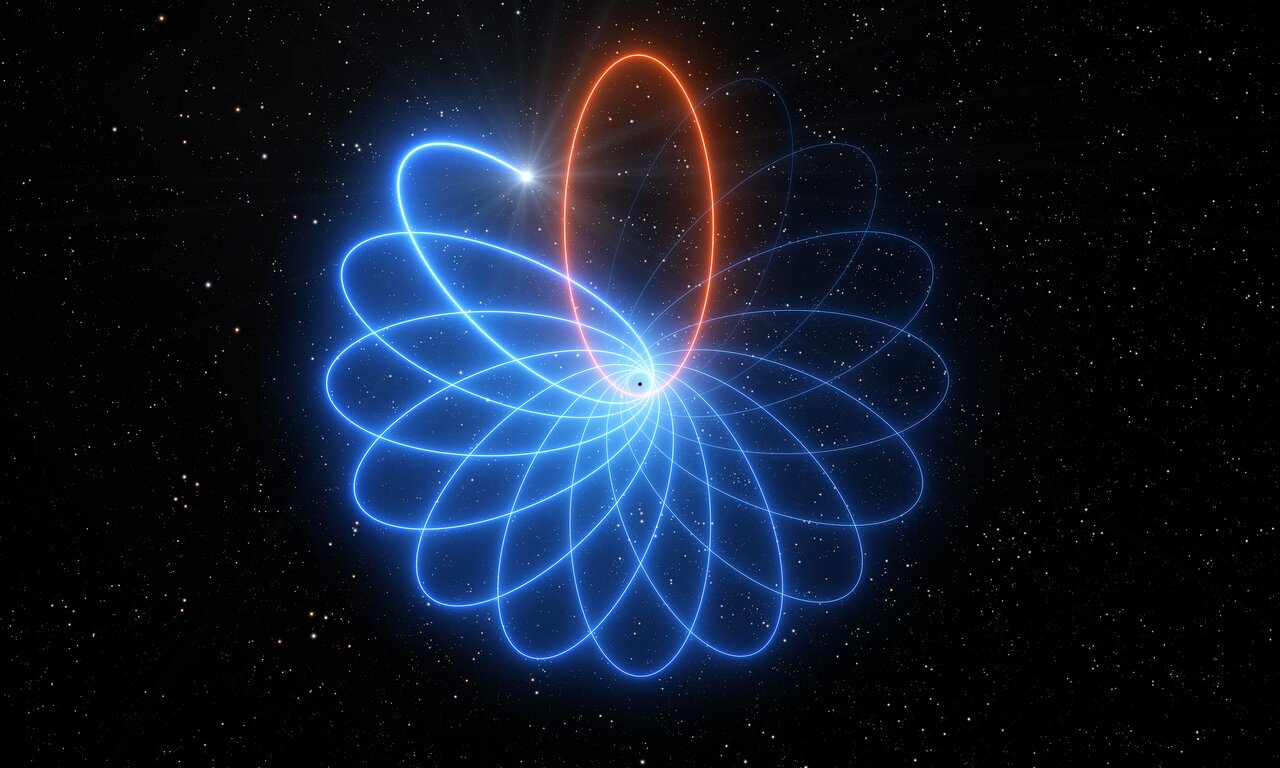

ESO's Very Large Telescope has observed a star dancing around the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. The observations have revealed, for the first time, that the star’s orbit is shaped like a rosette and not like an ellipse. The video is available in 4K UHD. The ESOcast Light is a series of short videos bringing you the wonders of the Universe in bite-sized pieces. The ESOcast Light episodes will not be replacing the standard, longer ESOcasts, but complement them with current astronomy news and images in ESO press releases. More information and download options: Receive future episodes on YouTube by pressing the Subscribe button abov e or follow us on Vimeo: Watch more ESOcast episodes: Find out how to view and contribute subtitles for the ESOcast in multiple languages, or translate this video on YouTube: Credit: ESO Directed by: Herbert Zodet. Editing: Herbert Zodet. Web and technical support: Gurvan Bazin and Raquel Yumi Shida. Written by: Caitlyn Buongiorno, Stephanie Rowlands and Bárbara Ferreira. Music: John Stanford – Deep Space (johnstanfordmusic.com). Footage and photos: ESO, L. Calçada and Daniele Gasparri (www.astroatacama.com). Scientific consultants: Paola Amico and Mariya Lyubenova. Caption author (Portuguese (Brazil)) Caroline M. Caption authors (Chinese (China)) Hd Ma 余庆抒 tabris trees Caption author (Greek) J Z Caption author (Polish) Joanna Kaczmarczyk Caption authors (Romanian) Răzvan Neagoe Daniela H.S. Caption author (Chinese (Taiwan)) Yawei C. Caption author (Chinese (Simplified)) cat calico Caption author (Portuguese) João Sant'Ana Caption author (Chinese) Yibo Cui Caption author (French (France)) David Jurado Caption author (Russian) Polina Anelikova Caption author (Spanish) David Jurado Caption authors (Italian) Cristina Bufi Poecksteiner Arianna Musso Barcucci Giovanna Fabiola Valverde Alessio Coci Caption author (Vietnamese) Sang Mai Thanh License Creative Commons Attribution license (reuse allowed)

This artist’s impression shows the path of the star S2 as it passes very close to the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

Observations made with ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) have revealed for the first time that a star, S2, orbiting the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way moves just as predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Most stars and planets have a non-circular orbit and therefore move closer and further away from the object they are rotating around. S2’s orbit precesses, meaning that the location of its closest point to the supermassive black hole changes with each turn, such that the next orbit is rotated with regard to the previous one, creating a rosette shape. This effect, known as Schwarzschild precession, had never before been measured for a star around a supermassive black hole. This animation shows S2’s orbit around Sagitarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of the Milky Way. The precession movement is exaggerated for easier viewing. More information and download options: Credit: MPE / TWENTYTWO Film

Most of what we know about black holes is based upon indirect evidence. General relativity predicts the structure of a black hole and how matter moves around it, and computer simulations based on relativity are compared with what we observe, from the accretion disks that swirl around a black hole to the immense jets of material they cast off at relativistic speeds. Then in 2019, radio astronomers captured the first direct image of the supermassive black hole in M87. This allows us to test the limits of relativity in a new and exciting way.

First direct image of the supermassive black hole in M87. Credit: Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration

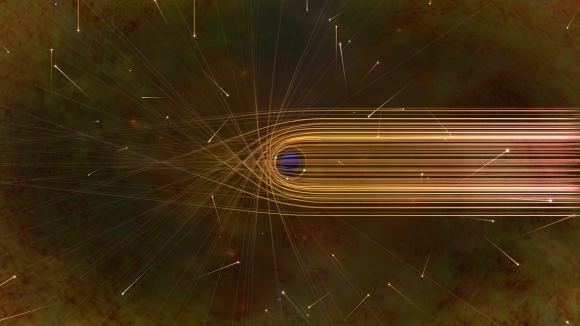

When a black hole is surrounded by hot gas, light can be focused by gravity to create a shadow of the black hole. Credit: Nicolle R. Fuller/NSF

This video shows a simple demonstration imitating gravitational lensing (using a wine glass stem) in the contexts of solar eclipses, quasars, and the cool appearances of galaxies (arc and rings).

Published on Jan 26, 2017 Objects with large masses such as galaxies or clusters of galaxies warp the spacetime surrounding them in such a way that they can create multiple images of background objects. This effect is called strong gravitational lensing. More information and download options: Credit: ESA/Hubble, NASA Category Science & Technology License Creative Commons Attribution license (reuse allowed)

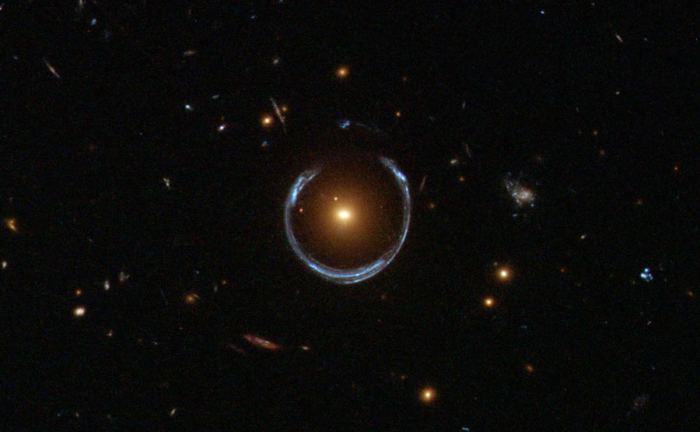

Hubble image of a luminous red galaxy (LRG) gravitationally distorting the light from a much more distant blue galaxy, a technique known as gravitational lensing. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA

Published on Feb 5, 2015 Gravity's a funny thing. Not only does it tug away at you, me, planets, moons and stars, but it can even bend light itself.

And once you're bending light, well, you've got yourself a telescope. Support us More stories Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Follow us on Tumblr: Like us on Facebook: Google+ - Instagram Team: Fraser Cain - @fcain Jason Harmer - @jasoncharmer Susie Murph - @susiemmurph Brian Koberlein - @briankoberlein Chad Weber - weber.chad@gmail.com Kevin Gill - @kevinmgill Created by: Fraser Cain and Jason Harmer Edited by: Chad Weber Music: Left Spine Down - “X-Ray”

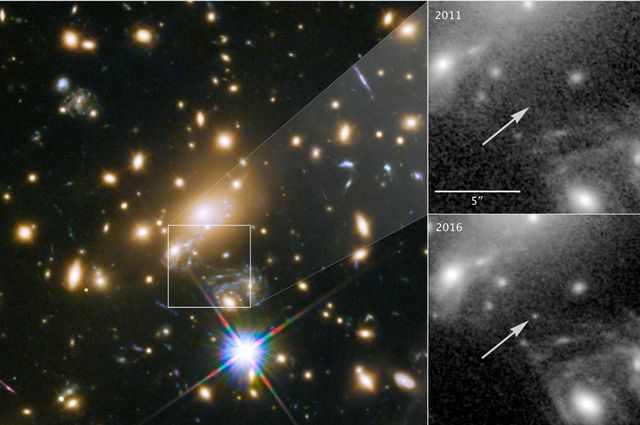

Icarus, the farthest individual star ever seen, shown at left. Panels at right show the view in 2011, without Icarus visible, compared with the star’s brightening in 2016. Credit: NASA, ESA and Patrick Kelly/University of Minnesota

This video shows the galaxy cluster MACS J1149.5+223. Thanks to a lucky alignment between the cluster, a dense object within it and a distant star, the image of the distant star was magnified by a factor of 2000, making it visible by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. Like the galaxy in which the star is located, the star is actually visible several times. However, the light from the second image of the star was redirected by another massive object in the cluster and only became visible when this object moved out of the line of sight. The video shows the position of the two images of the star within the cluster. More information and download options:

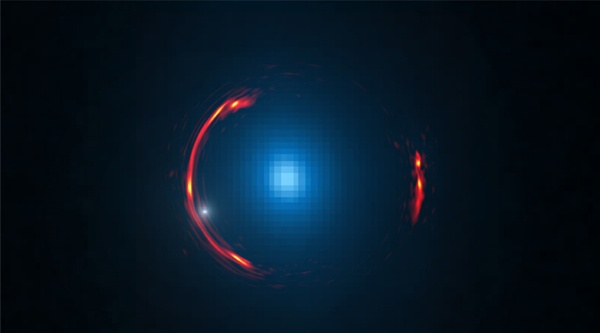

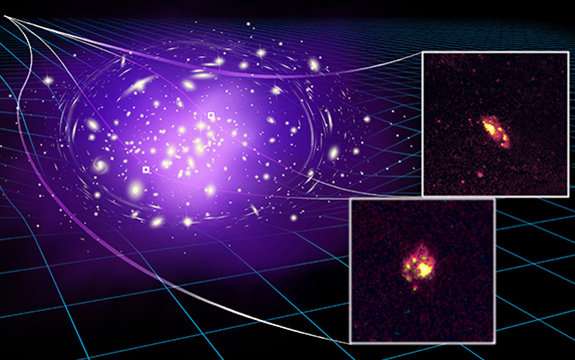

The large blue light is a lensing galaxy in the foreground, called SDP81, about 4 billion light years away.

The red arcs are the distorted image of a more distant galaxy, about 12 billion light years away.

By analyzing small distortions in the red, distant galaxy, astronomers have determined that a dwarf dark galaxy,

represented by the white dot in the lower left, is bound to SDP81.

The image is a composite from ALMA and the Hubble.

Image: Y. Hezaveh, Stanford Univ./ALMA (NRAO/ESO/NAOJ)/NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope

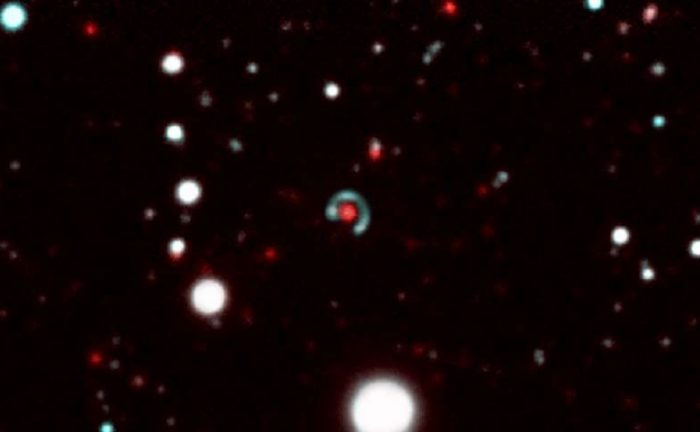

The "Canarias Einstein Ring." The green-blue ring is the source galaxy, the red one in the middle is the lens galaxy.

The lens galaxy has such strong gravity, that it distorts the light from the source galaxy into a ring.

Because the two galaxies are aligned, the source galaxy appears almost circular.

Image: This composite image is made up from several images taken with the DECam camera on the Blanco 4m telescope

at the Cerro Tololo Observatory in Chile.

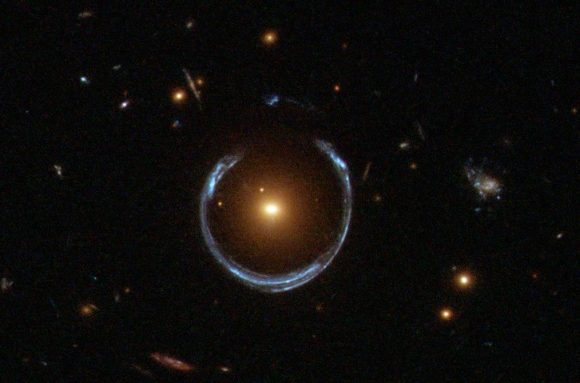

Another Einstein Ring. This one is named LRG 3-757. This one was discovered by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey,

but this image was captured by Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3. Image: NASA/Hubble/ESA

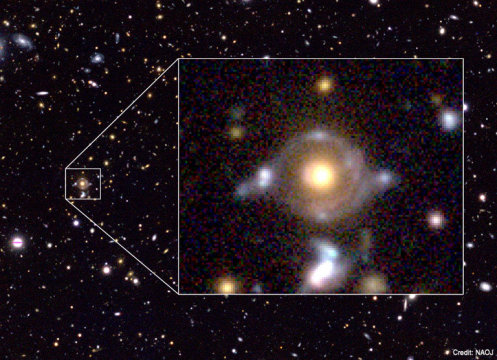

July 26, 2016 Source: National Astronomical Observatory of Japan Summary: Light from a distant galaxy can be strongly bent by the gravitational influence of a foreground galaxy.

That effect is called strong gravitational lensing. Normally a single galaxy is lensed at a time.

The same foreground galaxy can – in theory – simultaneously lens multiple background galaxies.

Although extremely rare, such a lens system offers a unique opportunity to probe the fundamental

physics of galaxies and add to our understanding of cosmology. One such lens system has recently been discovered

and the discovery was made not in an astronomer’s office, but in a classroom. It has been dubbed the Eye of Horus,

and this ancient eye in the sky may help us understand the history of the universe.

Eye of Horus in pseudo color. Enlarged image to the right (field of view of 23 arcseconds x 19 arcseconds)

show two arcs/rings with different colors. The inner arc has a reddish hue, while the outer arc has a blue tint.

There are also the lensed images of the background galaxies which are originally the same galaxies as the inner and the outer arcs.

The yellow-ish object at the center is a massive galaxy at z = 0.79 (distance 7 billion light years),

which bends the light from the two background galaxies. Credit: NAOJ

ALMA will consist of 66 individual antennae like these when it is complete.

The facility is located in the Atacama Desert in Chile, at 5,000 meters above sea level.

Credit: ALMA (ESO / NAOJ / NRAO)

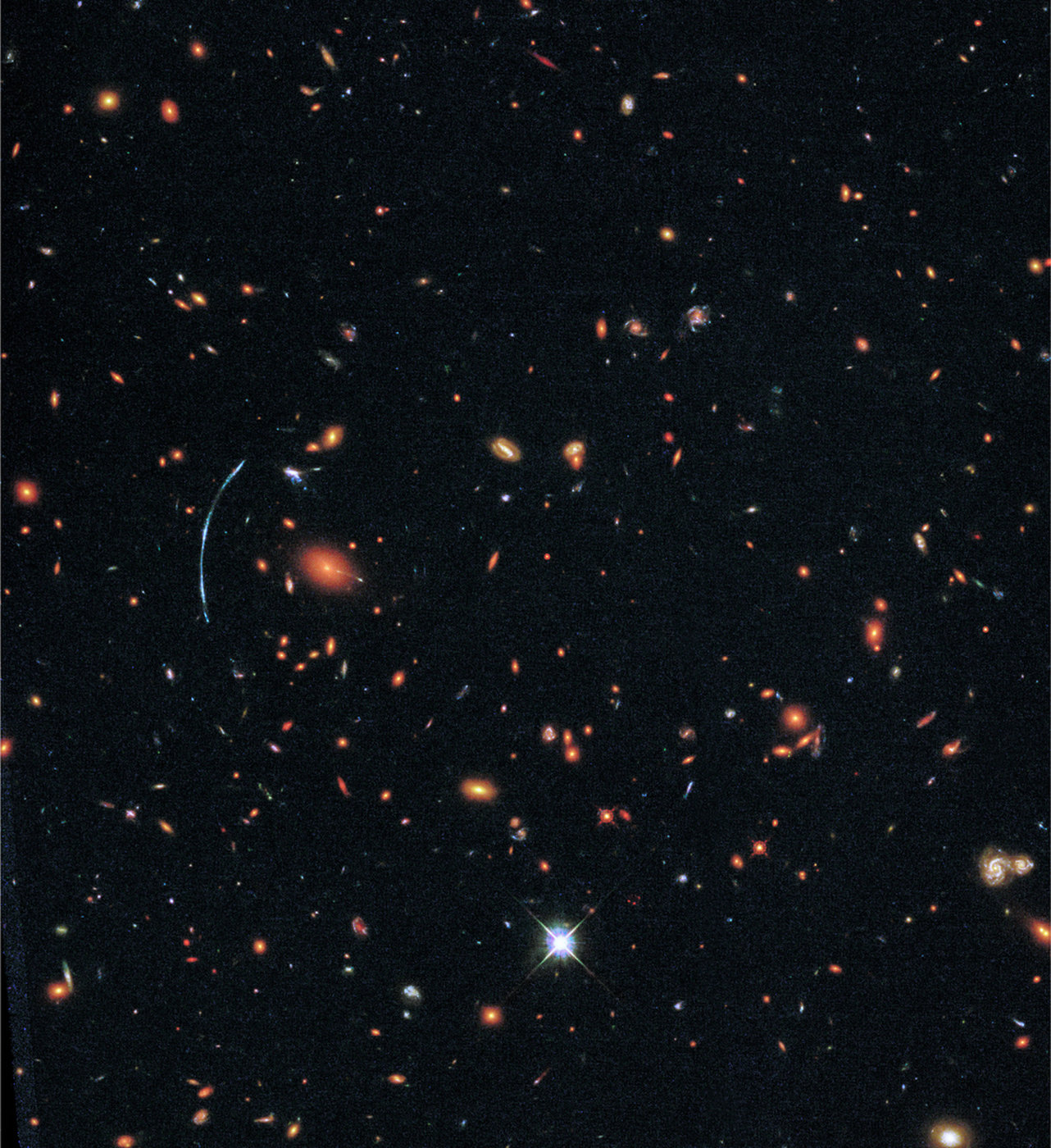

The view of a distant galaxy (nearly 10 billion light-years away) has been warped into a nearly 90-degree arc

of light by the gravity of the galaxy cluster known as RCS2 032727-132623 (about 5 billion light-years away).

Credit: NASA, ESA, J. Rigby (NASA GSFC), K. Sharon (KICP, U Chicago), and M. Gladders and E. Wuyts (U Chicago)

By Nola Taylor Redd, Space.com Contributor | July 8, 2017 07:53am ET

The Hubble Space Telescope captured this view of the galaxy cluster SDSS J1110+6459, which lies 6 billion light-years from Earth and contains hundreds of galaxies. Credit: T. Johnson/NASA/ESA A natural magnifying glass has sharpened images captured by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, revealing a distant galaxy that contradicts existing theories about early star formation. By pairing Hubble with a massive galaxy cluster, scientists captured images 10 times sharper than the space telescope could snap on its own.

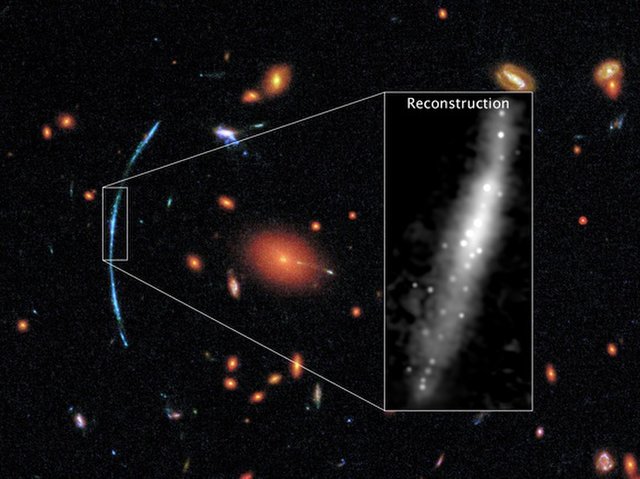

In this Hubble photograph of a distant galaxy cluster, a spotty blue arc stands out against a background

of red galaxies. The arc consists of three separate images of a galaxy in the background

called SGAS J111020.0+645950.8, which has been magnified and distorted through a process known as gravitational lensing.

Credit: T. Johnson/NASA/ESA

The newly spotted galaxy lies about 11 billion light-years from the sun.

Because of the connection between distance and time, that means astronomers

can see it as it looked 11 billion years ago, only a few billion years after the Big Bang

that kick-started the universe about 13.8 billion years ago.

Artist’s rendering of ULAS J1120+0641, a very distant quasar powered by a black hole with a mass two billion times

that of the Sun. Natural gravitational ‘microlenses’ can provide a way to probe these objects, and now a team of astronomers

have seen hints of quasar brightness changes that hint at their presence.

Image credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser.

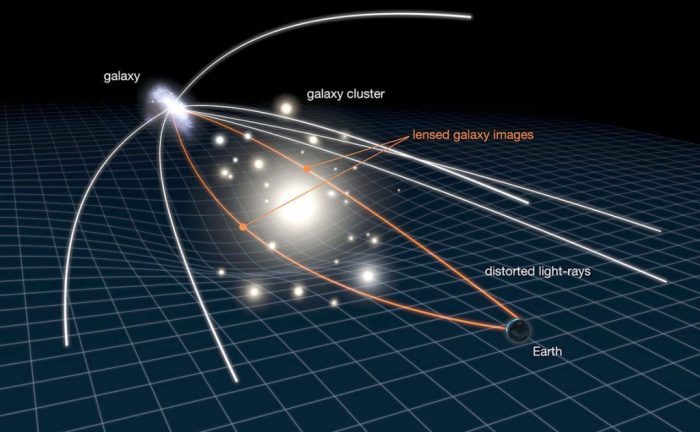

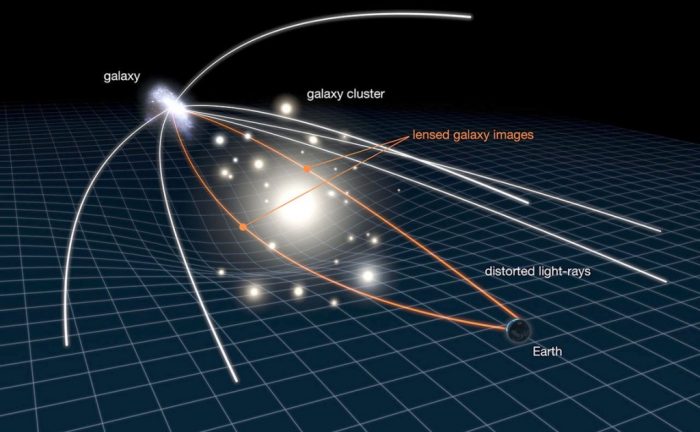

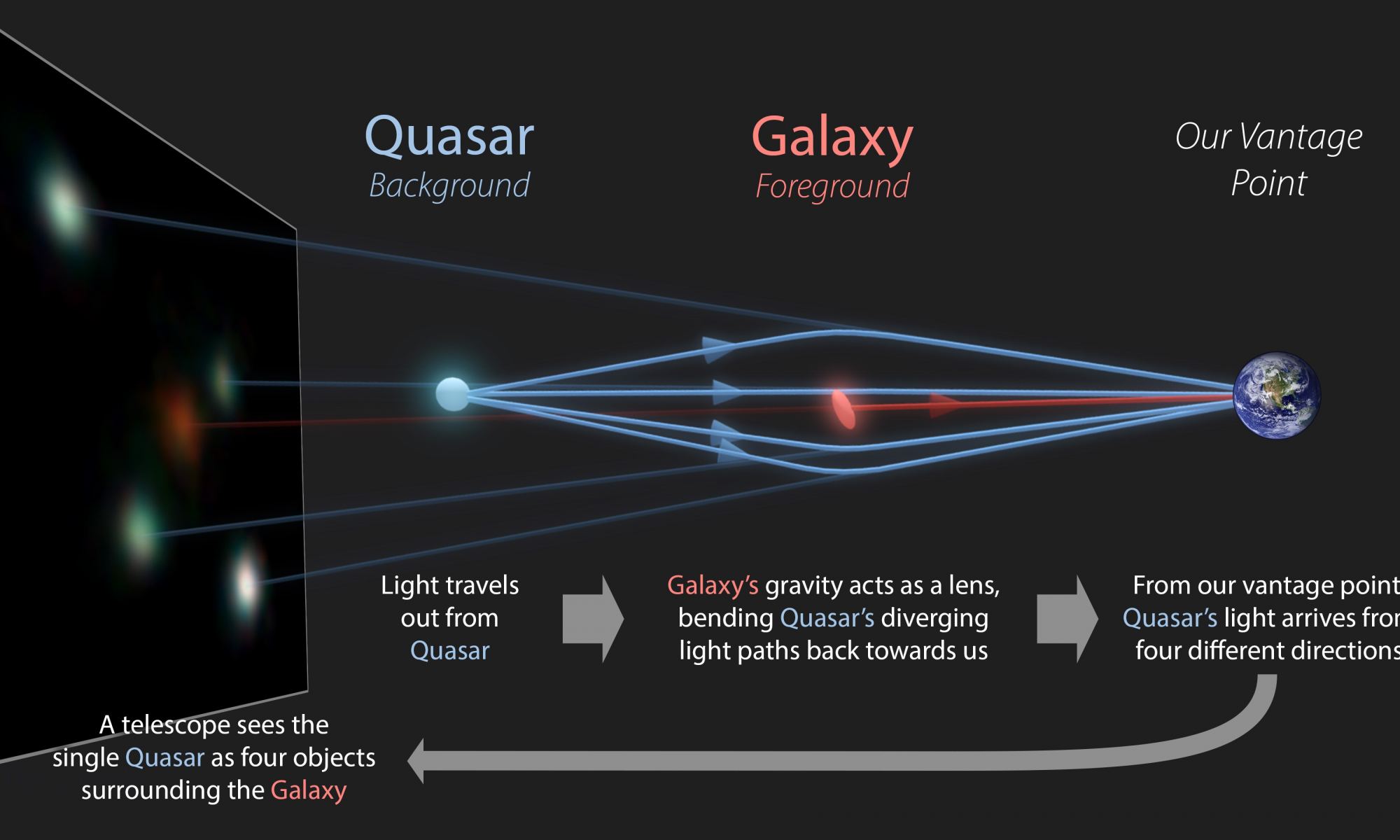

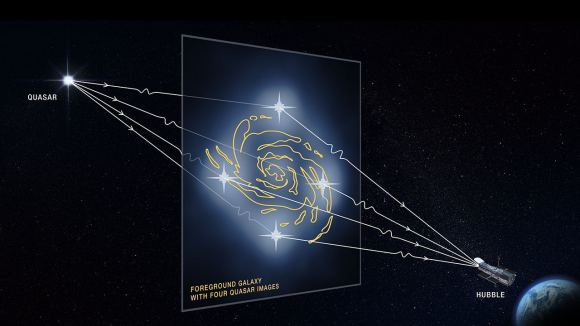

The technique of gravitational lensing relies on the presence of a large cluster of matter

between the observer and the object to magnify light coming from that object.

Credit: NASA

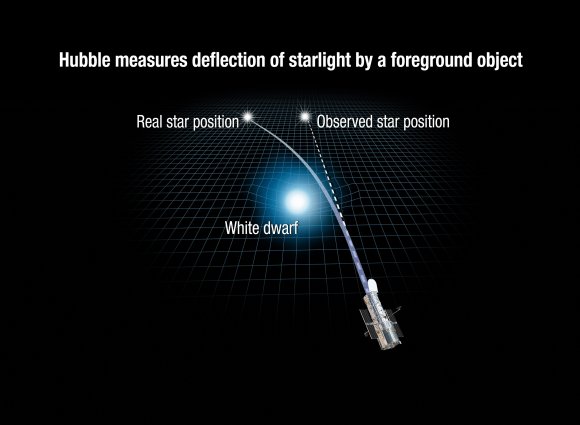

A Hubble image of the white dwarf star PM I12506+4110E (the bright object, seen in black in this negative print)

and its field which includes two distant stars PM12-MLC1&2.

Credit: Harding et al./NASA/HST

Hubble image showing the white dwarf star Stein 2051B and the smaller star below it appear to be close neighbors.

Credit: NASA/ESA/K. Sahu (STScI)

Illustration revealing how the gravity of a white dwarf star warps space and bends the light

of a distant star behind it.

Credits: NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI)

Animation showing the white dwarf star Stein 2051B as it passes in front of a distant background star.

Credit: NASA

Artist’s impression of the binary pair made up by a white dwarf star in orbit around Sirius (a white supergiant).

Credit: NASA, ESA and G. Bacon (STScI)

This illustration shows how gravitational lensing works. The gravity of a large galaxy cluster is so strong, it bends, brightens and distorts the light of distant galaxies behind it. The scale has been greatly exaggerated; in reality, the distant galaxy is much further away and much smaller. Credit: NASA, ESA, L. Calcada

The notable gravitational lens known as the Cosmic Horseshoe is found in Leo. Credit: NASA/ESA/Hubble

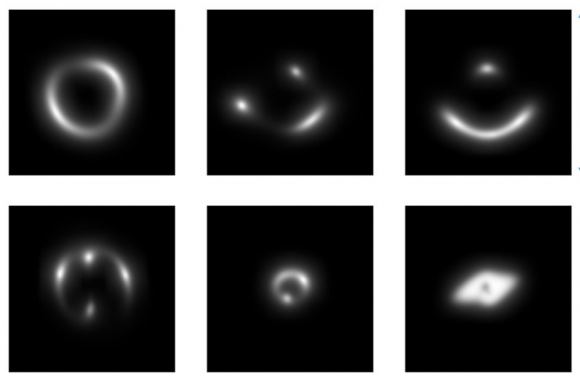

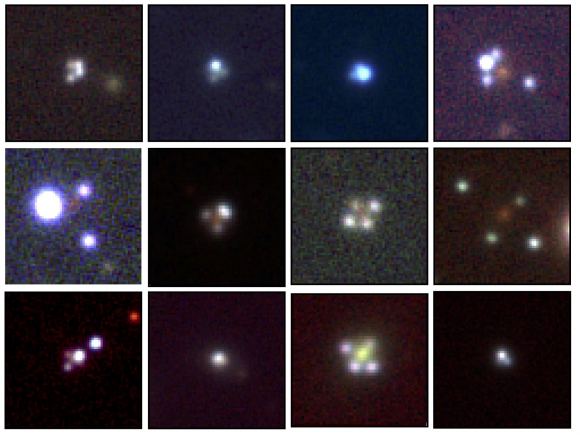

A sample of the handmade photos of gravitational lenses that the astronomers used to train their neural network. Credit: Enrico Petrillo/Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Spiral galaxy A1689B11 sits behind a massive cluster of galaxies that acts as a lens, producing two magnified images of the spiral galaxy in different positions in the sky. Credit: James Josephides

Composite image showing the discovery of the most distant known star using the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASA & ESA and P. Kelly (University of California, Berkeley)

This video shows the galaxy cluster MACS J1149.5+223. Thanks to a lucky alignment between the cluster, a dense object within it and a distant star, the image of the distant star was magnified by a factor of 2000, making it visible by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. Like the galaxy in which the star is located, the star is actually visible several times. However, the light from the second image of the star was redirected by another massive object in the cluster and only became visible when this object moved out of the line of sight. The video shows the position of the two images of the star within the cluster. More information and download options: Credit: ESA/Hubble, NASA.

This animation shows the effect of strong gravitational lensing, which can also be seen in the galaxy MACS J1149-2223 The mass of the galaxy cluster bends and magnifies the light of more distant objects in the background, making them appear brighter and hence allows telescopes to see them; it also leads to multiple images of the same object. This way Hubble detected the most distant star know to date, called LS1. More information and download options: Credit: ESA/Hubble, L. Calçada

Astronomers have used Hubble to make an incredible discovery — they have observed the most distant star ever seen. The bright blue star existed only 4.4 billion years after the Big Bang. This incredible distant star allows astronomers to learn more about the formation and evolution of stars in the early Universe. More information and download options: Subscribe to Hubblecast in iTunes! Receive future episodes on YouTube by pressing the Subscribe button above or follow us on Vimeo: Watch more Hubblecavideo.web_category.allst episodes: Credit: Directed by: Mathias Jäger Visual design and editing: Nico Bartmann Written by: Mathias Jäger Images: ESA/Hubble, NASA Videos: ESA/Hubble, L. Calçada, M. Kornmesser Animations: NASA, ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser, L. Calçada Music: John Stanford (johnstanfordmusic.com) Web and technical support: Mathias Andre and Raquel Yumi Shida Executive producer: Lars Lindberg Christensen

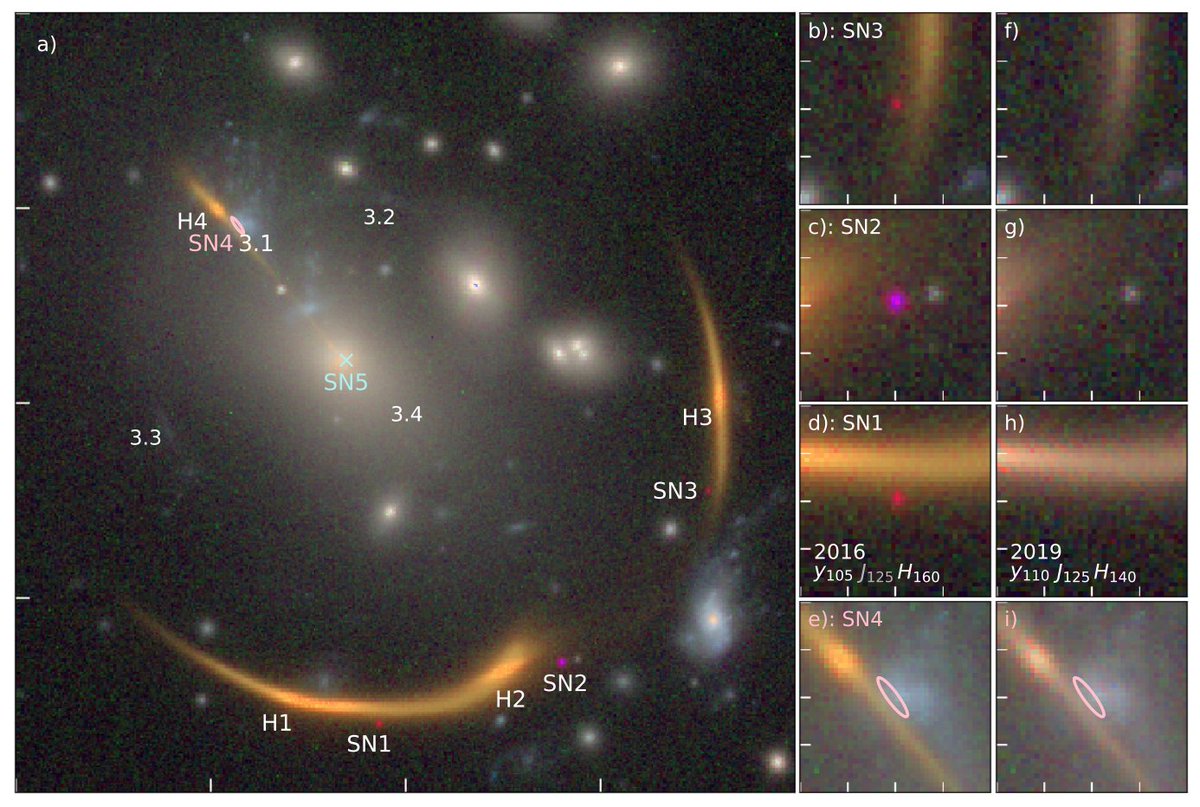

Image of the MAC J0138.02155 cluster and gravitationally lensed MRG-M0138 galaxy showing the locations of the three observed instances of the supernova (SN1-3) and the expected location of the fourth instance (SN4), estimated to appear around 2037. Credit – Rodney, Brammer et al.

Good telescope that I've used to learn the basics: Get a Wonderful Person shirt: Alternatively, : PayPal donations can be sent here Hello and welcome! My name is Anton and in this video, we will talk about a quadruply lensed supernova detected using Hubble telescope Paper: (PDF) You can buy Universe Sandbox 2 here : Or get a shirt You can buy Universe Sandbox 2 game here: Hello and welcome! My name is Anton and in this video, we will talk about a detection of the first Earth like planet by TESS telescope. : Find all of the data you can analyze yourself here And the detection paper is here: Support this channel on Patreon to help me make this a full time job: Space Engine is available for free here: Enjoy and please subscribe. Twitter: Facebook: Twitch: Bitcoins to spare? Donate them here to help this channel grow! 1GFiTKxWyEjAjZv4vsNtWTUmL53HgXBuvu The hardware used to record these videos: CPU: Video Card: Motherboard: RAM: PSU: Case: Microphone: Mixer: Recording and Editing: Thank you to all Patreon supporters of this channel Special thanks also goes to all the wonderful supporters of the channel through YouTube Memberships: Tybie Fitzhugh Viktor Óriás Les Heifner theGrga Steven Cincotta Mitchell McCowan Partially Engineered Humanoid Alexander Falk Drew Hart Arie Verhoeff Aaron Smyth Mike Davis Greg Testroet John Taylor EXcitedJoyousWorldly ! Christopher Ellard Gregory Shore maggie obrien Matt Showalter Tamara Franz R Schaefer diffuselogic Grundle Muffins Images/Videos: NASA, ESA, A. NIERENBERG (JPL), AND T. TREU AND D. GILMAN (UCLA) ESA/HUBBLE & NASA NASA, ESA, AND STSCI NASA, ESA AND D. PLAYER (STSCI) NASA, ESA, A. NIERENBERG (JPL), AND T. TREU AND D. GILMAN (UCLA) R. Hurt, IPAC & Caltech / Gaia Gravitational Lenses group. Leiden Institute of Physics , Gravitational Lensing of a Distant star Forming Galaxies Gravitational Lensing of a Distant star Forming Galaxies Schematic Artist impression of a Gravitational lensing of a distant Merger ESO

The Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation is the afterglow of the Big Bang; one of the strongest lines of evidence we have that this event happened. UCLA's Dr. Ned Wright explains.

Gravity's a funny thing. Not only does it tug away at you, me, planets, moons and stars, but it can even bend light itself. And once you're bending light, well, you've got yourself a telescope. Support us at: More stories at: Twitter: @universetoday Facebook: Instagram - What Fraser's Watching Playlist: Our Book is out! Audio Podcast version: ITunes: RSS: Sign up to my weekly email newsletter: Support us at:Support us at: Follow us on Tumblr: : More stories at Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Like us on Facebook: Instagram - Team: Fraser Cain - @fcain / frasercain@gmail.com /Karla Thompson - @karlaii Chad Weber - Chloe Cain - Instagram: @chloegwen2001 Music: Left Spine Down - “X-Ray” SFIA Discord Server: Support us at: More stories at: Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Follow us on Tumblr: Like us on Facebook: Instagram -

Cosmologists tell us that the Universe is flat. It sure feels like 3-dimensions. What does this even mean, and how do we know it’s true? Support us at: More stories at: Twitter: @universetoday Facebook: Instagram - What Fraser's Watching Playlist: Our Book is out! Audio Podcast version: ITunes: RSS: Sign up to my weekly email newsletter: Support us at:Support us at: Follow us on Tumblr: : More stories at Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Like us on Facebook: Instagram - Team: Fraser Cain - @fcain / frasercain@gmail.com /Karla Thompson - @karlaii Chad Weber - Chloe Cain - Instagram: @chloegwen2001 Music: Left Spine Down - “X-Ray” SFIA Discord Server: Support us at: More stories at: Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Follow us on Tumblr: Like us on Facebook: Instagram -

Support us at: More stories at: Twitter: @universetoday Facebook: Instagram - What Fraser's Watching Playlist: Our Book is out! Audio Podcast version: ITunes: RSS: Sign up to my weekly email newsletter: Support us at:Support us at: Follow us on Tumblr: : More stories at Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Like us on Facebook: Instagram - Team: Fraser Cain - @fcain / frasercain@gmail.com /Karla Thompson - @karlaii Chad Weber - Chloe Cain - Instagram: @chloegwen2001 Music: Left Spine Down - “X-Ray” SFIA Discord Server: Support us at: More stories at: Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Follow us on Tumblr: Like us on Facebook: Instagram -

Check Out These Gravitational Lenses Imaged by Webb During its First Run

A collage of eight Webb images of gravitational lensing, each showing various distorted galaxies in the center of each frame. Credit: ESA/NASA/CSA

*Nicknamed "The COSMOS-Web Ring," this lensing system contains a massive elliptical galaxy that acts as the gravitational lens and a more distant star-forming galaxy whose light has been stretched into a perfect circle. Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, G. Gozaliasl, A. Koekemoer, M. Franco*

A central glowing galaxy in the foreground has a warped galaxy from the background as an orange arc along its right side. Credit: ESA/Webb, NASA & CSA, G. Gozaliasl, A. Koekemoer, M. Franco*

Click here to Click here to Jump to Associated pages from Universetoday

Click here to return to top of page

Detection of an unusually bright X-Ray flare from Sagittarius A*, a supermassive black hole in the center of the Milky Way galaxy. Credit: NASA/CXC/Stanford/I. Zhuravleva et al.

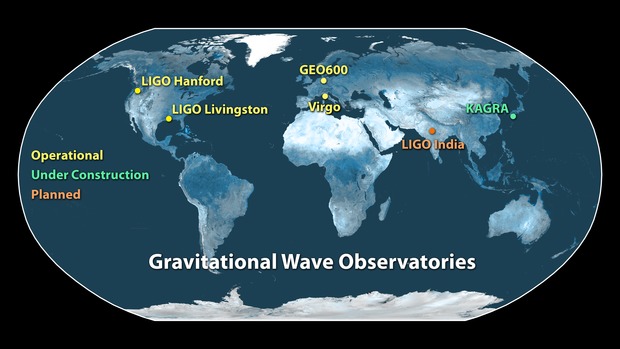

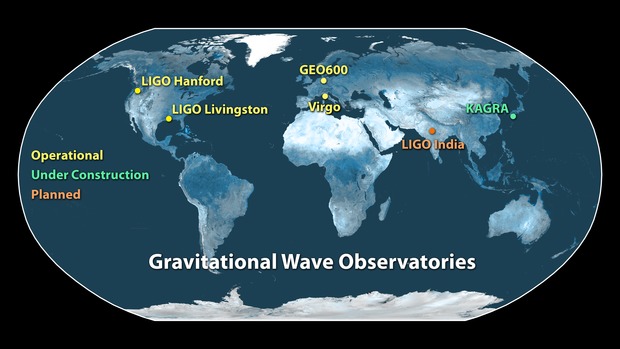

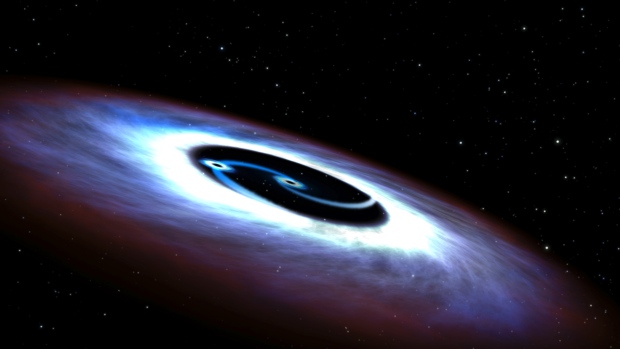

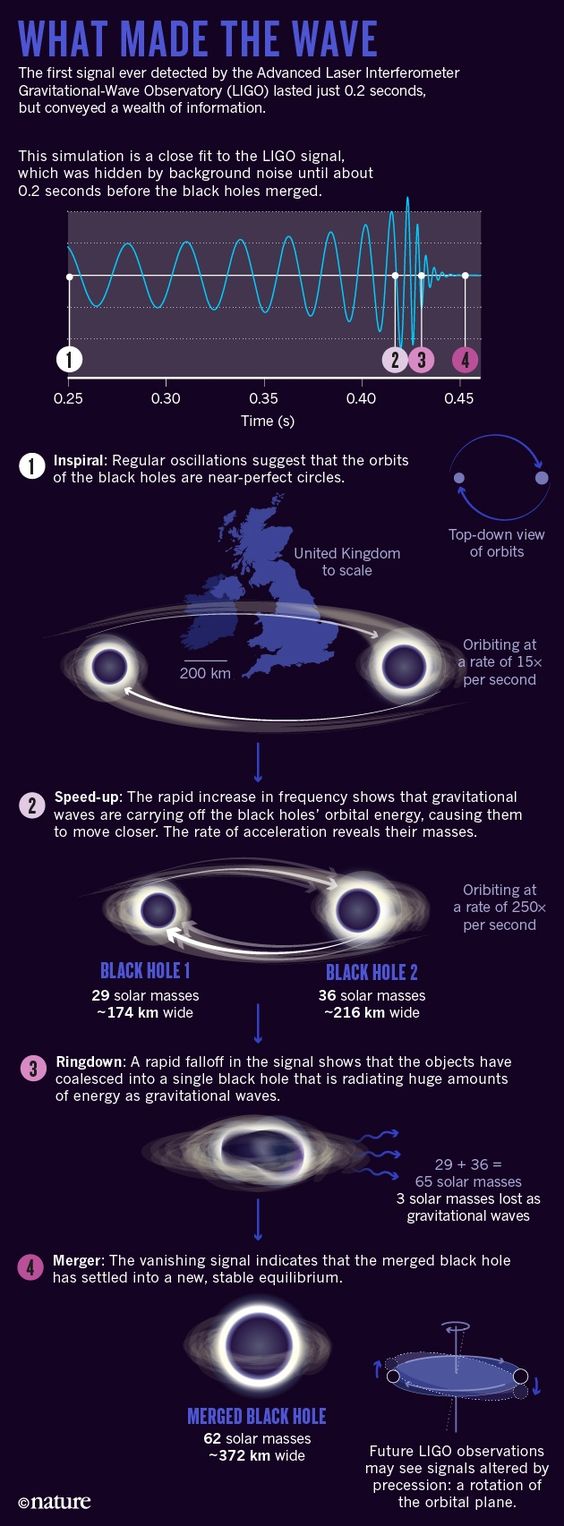

Caption This is the LIGO signal that heralded the era of gravitational wave astronomy. Credit Caltech/MIT/LIGO Lab

Published on Jun 15, 2016 The best-fit models of LIGO’s gravitational-wave signals are converted into sounds.

The first sound is from modeled gravitational waves detected by LIGO on Dec. 26, 2015, when two black holes merged.

This is then compared to the first-ever gravitational waves detected by LIGO on Sept. 14, 2015, when two higher-mass black holes merged.

This sequence is repeated. The pitch of both signals is then increased, allowing them to be heard more easily,

and this sequence is also repeated. Category Education License Standard YouTube License

Published on Jun 15, 2016 For the second time, scientists have directly detected gravitational waves — ripples through the fabric of space-time,

created by extreme, cataclysmic events in the distant universe Learn more

The team has determined that the incredibly faint ripple that eventually reached Earth was produced by two black holes colliding

at half the speed of light, 1.4 billion light years away. Video produced and edited by Melanie Gonick/MIT Two Black Holes Merge into One simulation: SXS LIGO's First Observing Run timeline image: LIGO Ripples in Spacetime Pond animation: LIGO/T. Pyle Black Holes withKnown Masses image: LIGO Comparing "Chirps" from Black Holes animation: LIGO Spiral Dance of Black Holes still image: LIGO/T. Pyle Category Science & Technology License Standard YouTube License

[Artist Impression of the Big Bang] 20 Jun 2016 at 07:02, Katyanna Quach The first time physicists announced that the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO)

had detected gravitational waves, on September 14, 2015, it was breaking news. The discovery coincided with the

100-year anniversary of Einstein's theory of General Relativity, which predicted the existence of gravitational waves.

Last week's announcement that LIGO had detected a second round of gravitational waves proved that the first signal was not a fluke.

The tremendous effort from thousands of physicists, engineers and computer scientists to design, build, and maintain LIGO,

and analyse its results, have paid off. The detector is alive and working well – uncovering signals from the most violent events

happening in our universe.

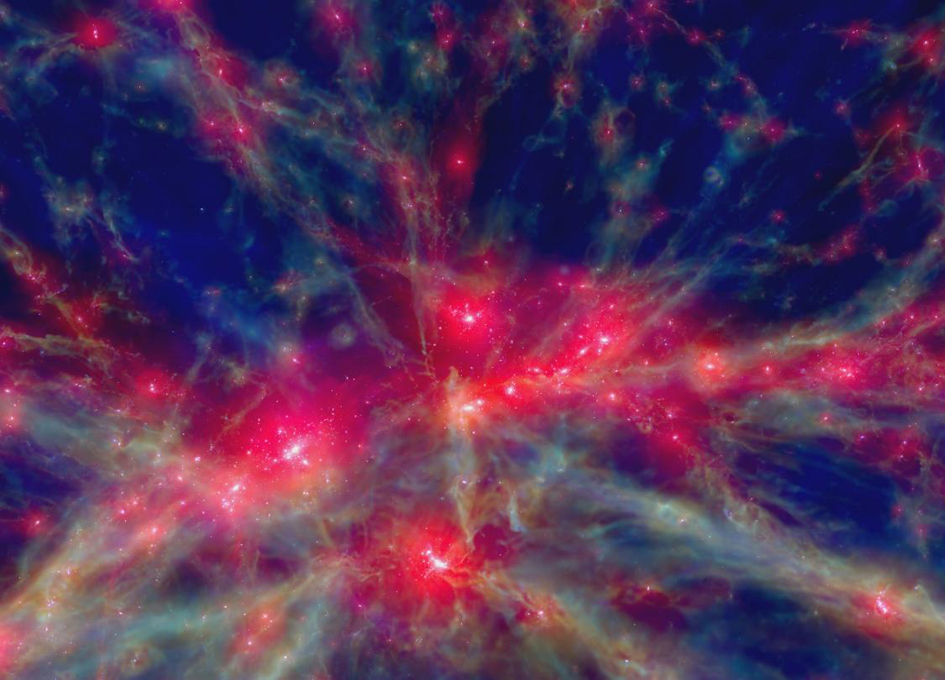

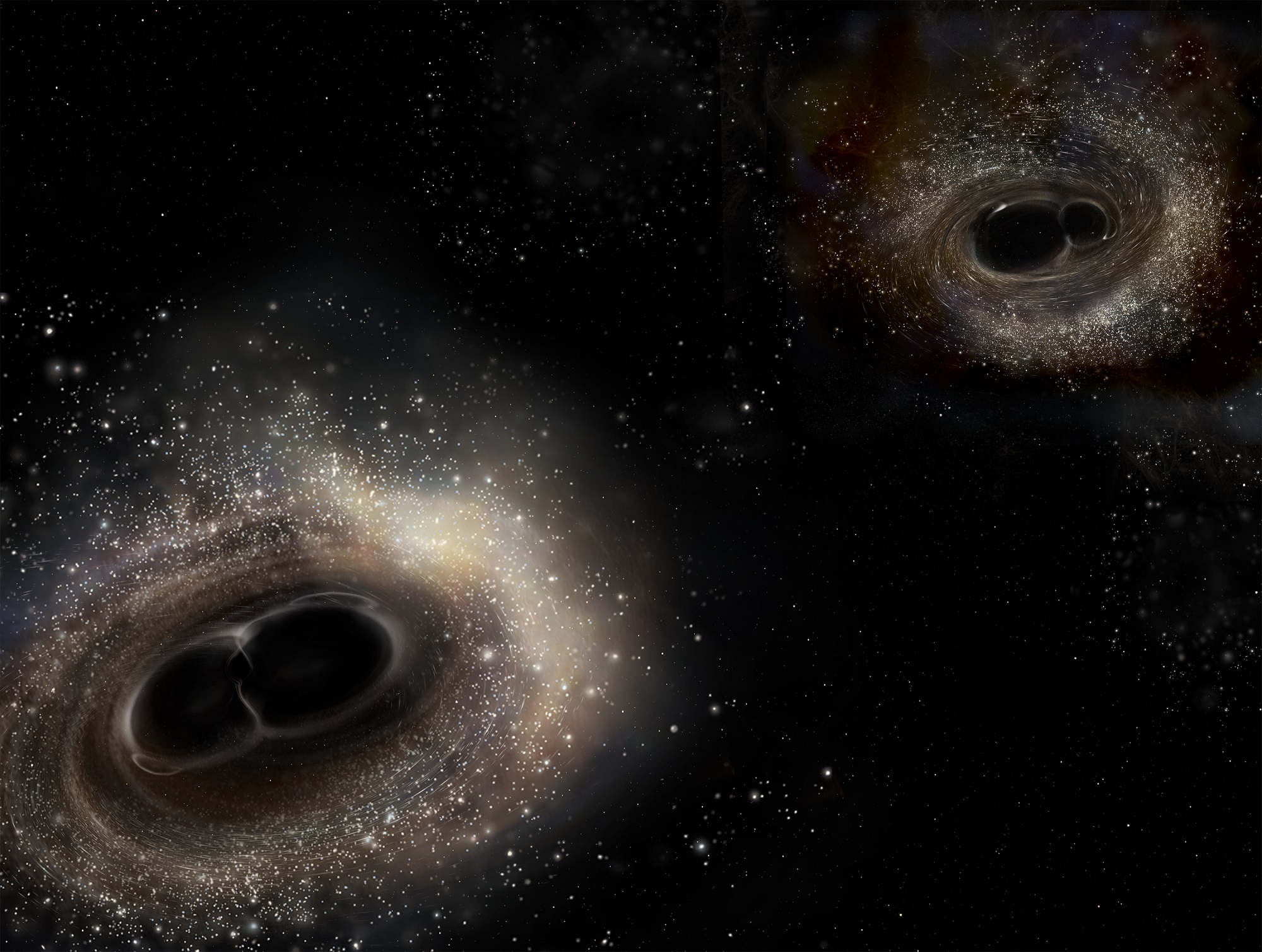

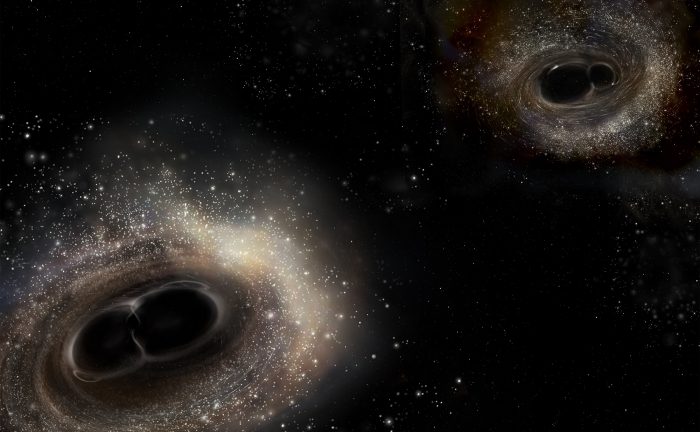

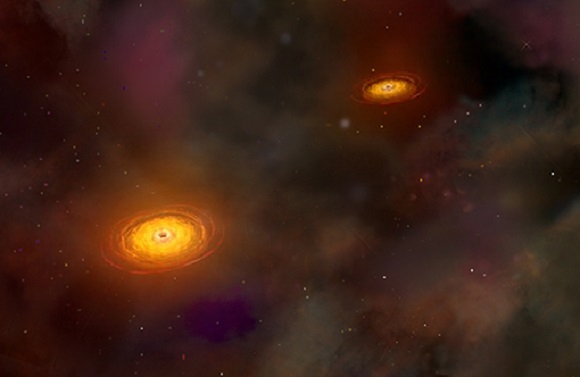

Scientists led by Durham University's Institute for Computational Cosmology ran the huge cosmological simulations

that can be used to predict the rate at which gravitational waves caused by collisions between the monster black holes might be detected.

The amplitude and frequency of these waves could reveal the initial mass of the seeds from which the first black holes grew

since they were formed 13 billion years ago and provide further clues about what caused them and where they formed, the researchers said.

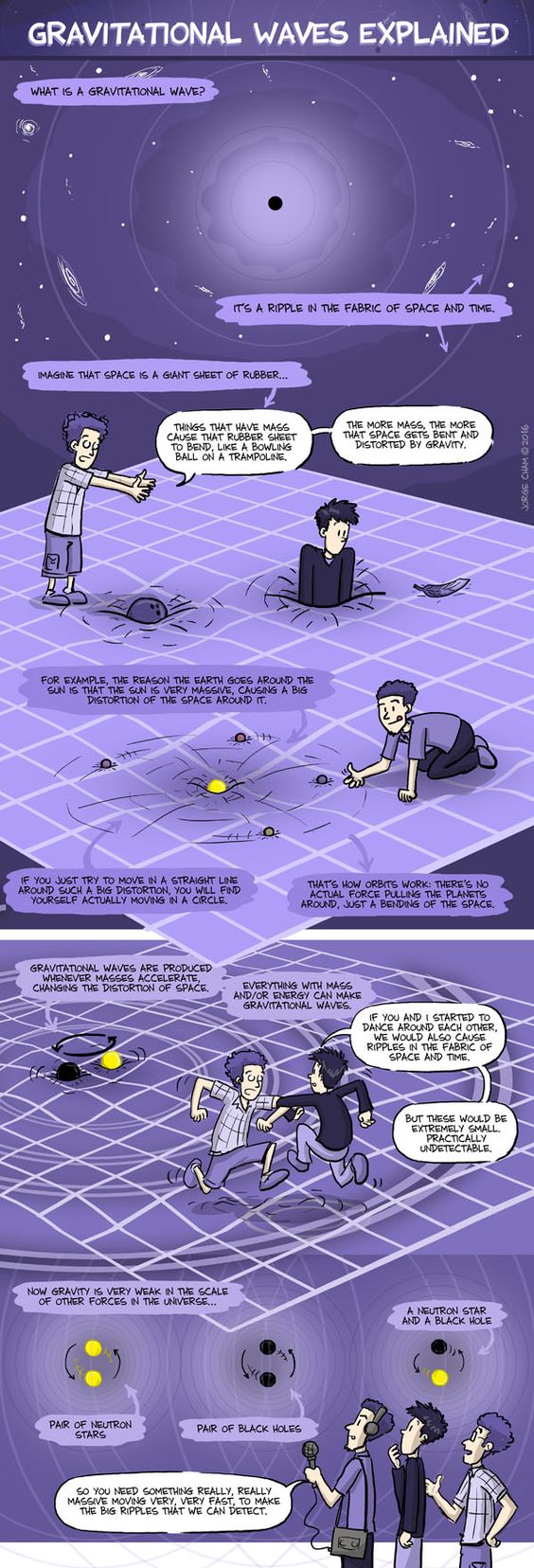

In February of 2016, scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) made history by announcing the first-ever detection of gravitational waves (GWs). These ripples in the very fabric of the Universe, which are caused by black hole mergers or white dwarfs colliding, were first predicted by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity roughly a century ago.

Computer calculations modeling the gravitational waves LIGO has observed to date and the black holes that emitted the waves. The image shows the horizons of the black holes above the corresponding gravitational wave. Credit: Teresita Ramirez / Geoffrey Lovelace / SXS Collaboration / LIGO Virgo Collaboration. Inspired by the Kepler Orrery IV Inspired by the Kepler Orrery IV

Published on Jun 8, 2015 When massive objects crash into each other, there should be a release of gravitational waves. So what are these things and how can we detect them? Support us More stories at: Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Follow us on Tumblr Like us on Facebook Google+ - Instagram - Created by: Fraser Cain and Jason Harmer Edited by: Chad Weber Music: Left Spine Down - “X-Ray” Who wants to bet against Einstein? You? You? What about you?

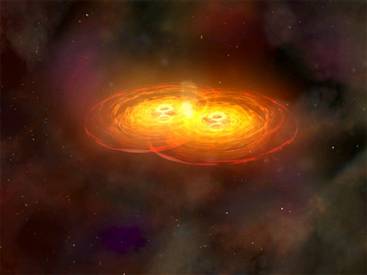

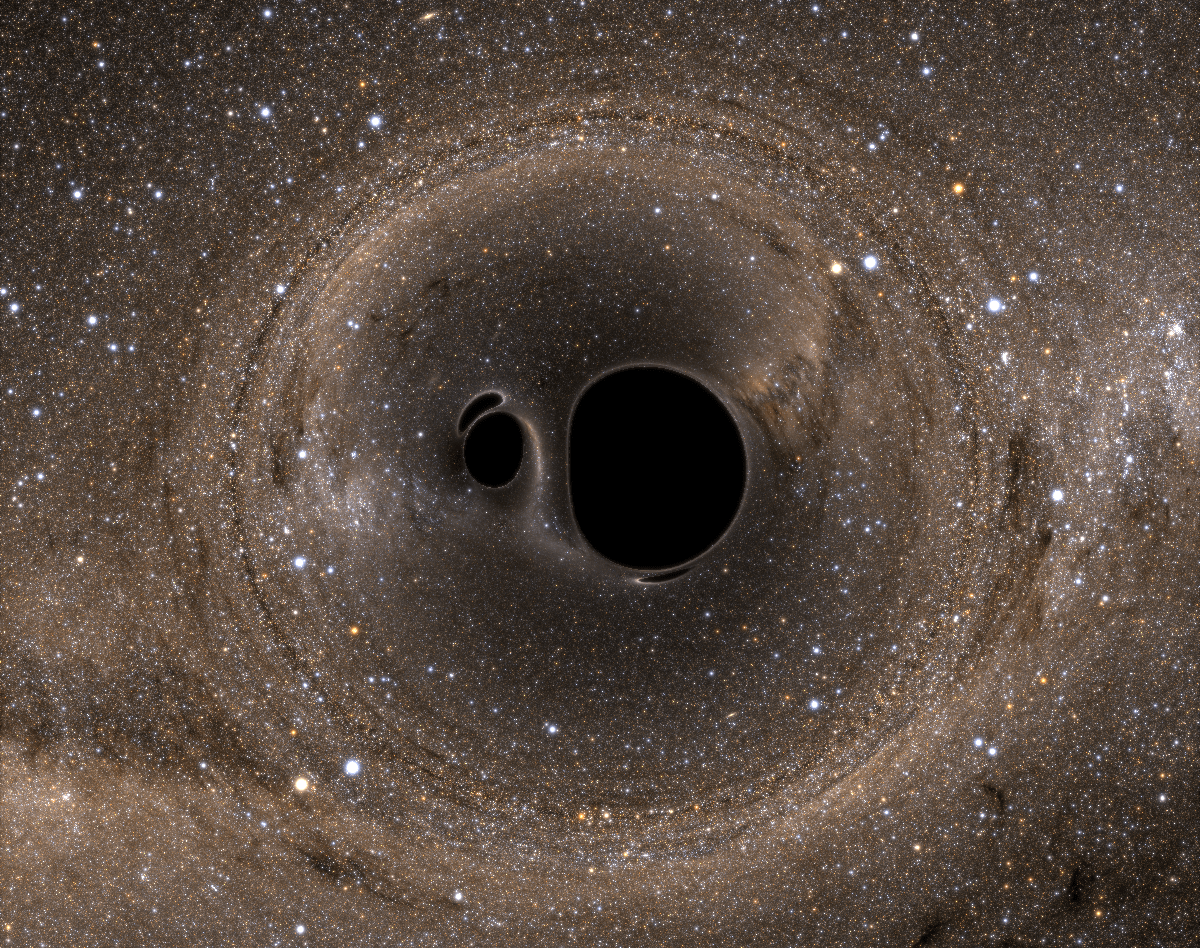

LIGO Lab Caltech : MIT Published on Jun 15, 2016 This artist's animation shows the merger of two black holes and the gravitational waves that ripple outward during the event. The black holes—which represent those detected by LIGO on Dec. 26, 2015 —were 14 and 8 times the mass of the sun, until they merged, forming a single black hole 21 times the sun's mass. One solar mass was converted to gravitational waves. In reality, the area near the black holes would appear highly warped, and the gravitational waves would be difficult to see directly. Credit: LIGO/T. Pyle

LIGO’s two facilities, located in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington. Credit:Ligo.caltech.edu

An artist’s impression of two merging black holes. Image: NASA/CXC/A. Hobart

In February 2016, LIGO detected gravity waves for the first time. As this artist's illustration depicts, the gravitational waves were created by merging black holes. Credit: LIGO/A. Simonnet.

LIGO’s two facilities, located in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington. Credit:Ligo.caltech.edu

Published on Feb 11, 2016 Watch Monash astrophysicists and LIGO Scientific Collaborators Dr Eric Thrane and Dr Paul Lasky describe the incredible event which took place about 1.4 billion years ago, generating the first ever gravitational wave to be detected on 14 September 2015 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) detectors in the USA. They describe the moment of realisation that this was a real gravitational wave, the significance of the detection and how it could unlock the secrets of the universe.

HERE Is

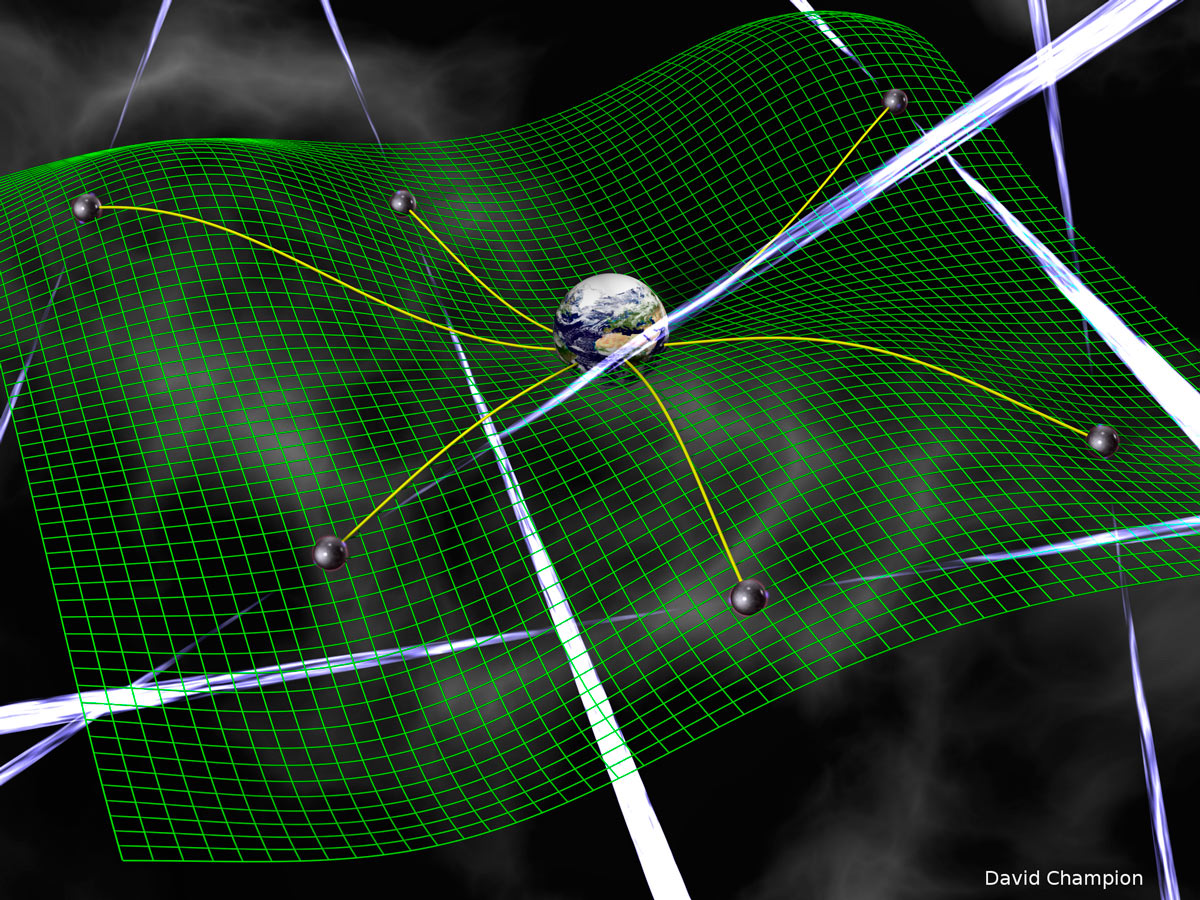

Gravitational waves are thought to cause a rippling effect on spacetime.

Published on Jun 15, 2016 Read more: The pair of black holes responsible for the first ever detected gravitational wave may have been spat out of a mosh pit at the center of a globular star cluster. Category Science & Technology License Standard YouTube License

New gravitational wave detection shows shape of ripples from black hole collision

Gravitational wave article from the Guardian

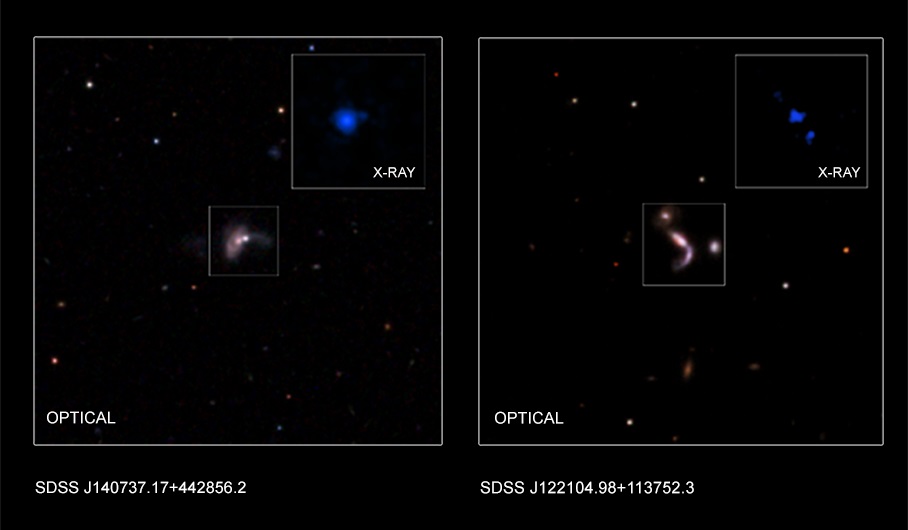

SCIENTIST FIND TREASURE TROVE OF GIANT BLACK HOLE PAIRS

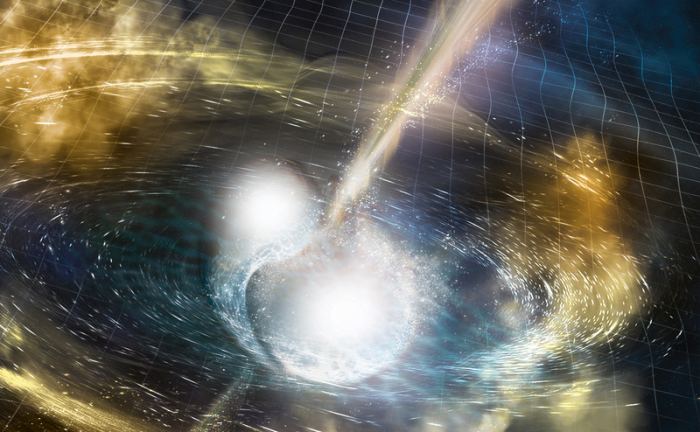

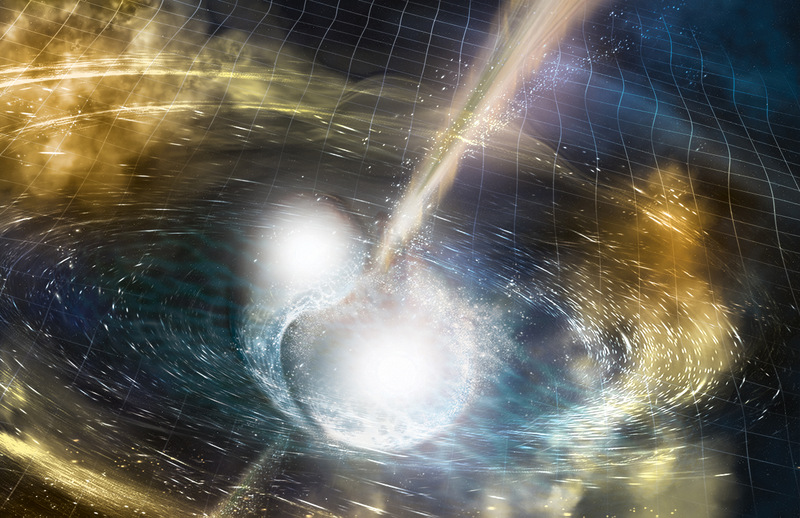

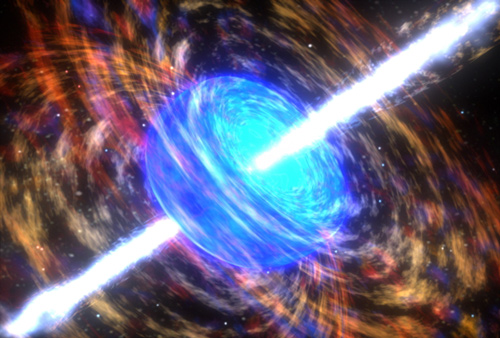

Artist's illustration of two merging neutron stars. The narrow beams represent the gamma-ray burst while the rippling spacetime grid indicates the isotropic gravitational waves that characterize the merger. Swirling clouds of material ejected from the merging stars are a possible source of the light that was seen at lower energies. Credit: National Science Foundation/LIGO/Sonoma State University/A. Simonnet

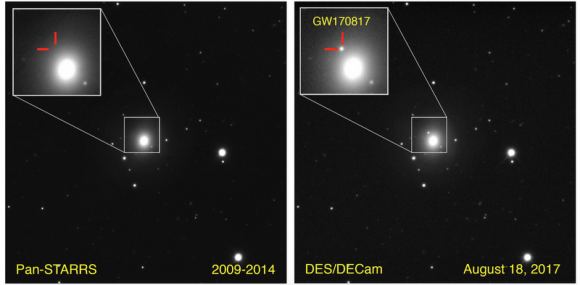

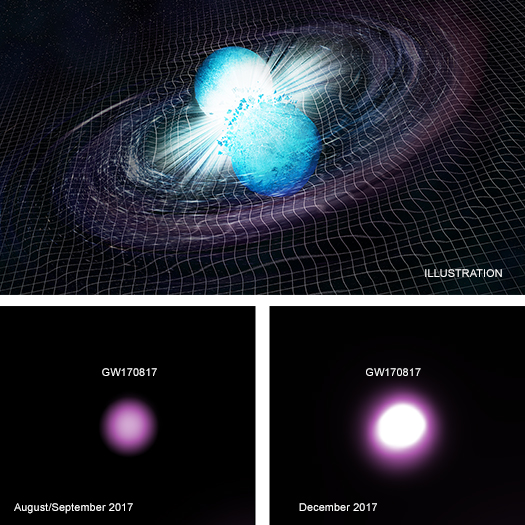

Observations of the kilonova. Credit: P.K. Blanchard/ E. Berger/ Pan-STARRS/DECam.

This animation shows how LIGO, Virgo, and space- and ground-based telescopes zoomed in on the location of gravitational waves detected August 17, 2017 by LIGO and Virgo. By combining data from the Fermi and Integral space missions with data from LIGO and Virgo, scientists were able to confine the source of the waves to a 30-square-degree sky patch. Visible-light telescopes searched a large number of galaxies in that region, ultimately revealing NGC 4993 to be the source of gravitational waves. :More information and download options Credit: LIGO-Virgo

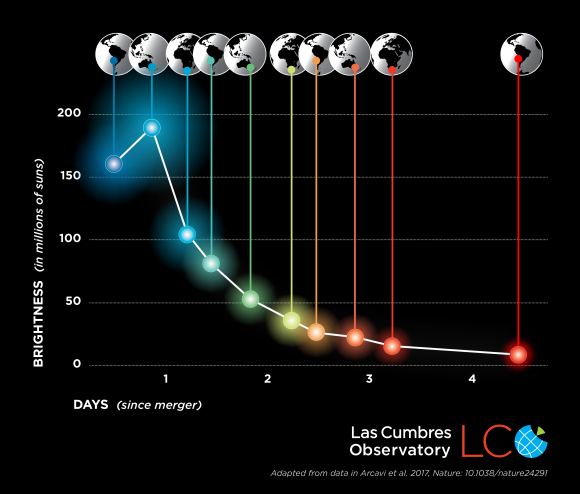

The kilonova became red and faded by a factor of over 20 in just a few days. This rapid change was captured by Las Cumbres Observatory telescopes as night time moved around the globe. Credit: Sarah Wilkinson / LCO.

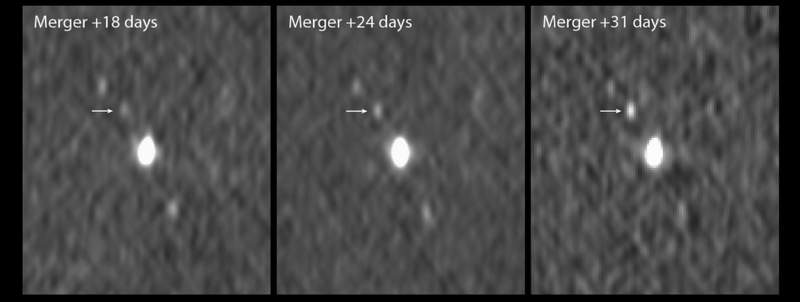

On 17 August 2017, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and the Virgo Interferometer both detected gravitational waves from the collision between two neutron stars. Within 12 hours observatories had identified the source of the event within the lenticular galaxy NGC 4993, shown in this image gathered with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. The associated stellar flare, a kilonova, is clearly visible in the Hubble observations. This is the first time the optical counterpart of a gravitational wave event was observed. Hubble observed the kilonova gradually fading over the course of six days, as shown in these observations taken in between 22 and 28 August (insets). Credit: NASA and ESA. Acknowledgment: A.J. Levan (U. Warwick), N.R. Tanvir (U. Leicester), and A. Fruchter and O. Fox (STScI).

This is the first optical image ever to show an event initially detected as a Gravitational Wave (GW), designated GW170817, shown left. Afterglow, designated as SSS17a, is left over from the explosion of two neutron stars that collided in galaxy NGC 4993 (shown centre). Only 10.9 hours after triggering the largest astronomical search in history, GW170817’s afterglow was discovered by the Swope 1-m telescope at the Las Campanas Observatory, in Chile. Four days later, image on right shows afterglow dimming in brightness and changing from blue to red. CREDIT: Las Campanas Observatory, Carnegie Institution of Washington (Swope + Magellan)

ANIMATION (you may have to click image for animation in some browsers): This time-lapse image of the afterglow of GW170817 shows it continuing to increase in radio wavelength brightness over the first month, and was provided by the National Radio Astronomy Observatory Very Large Array radio telescope. CREDIT: NRAO/VLA

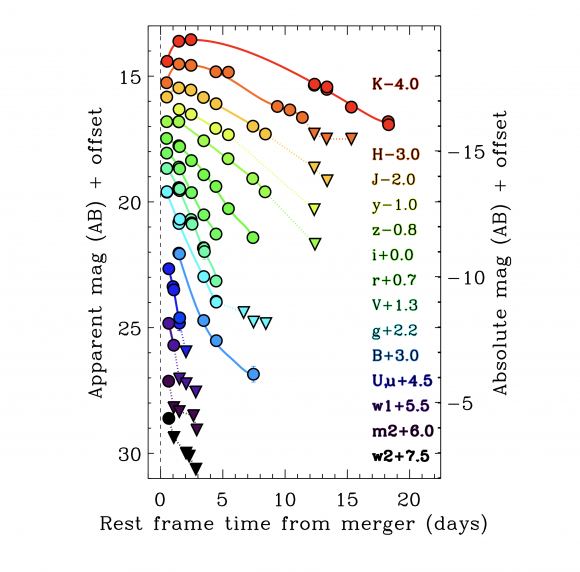

Change in brightness of GW170817’s afterglow over time since explosion (merger), is shown in these light-curves. Brightness in 14 different optical wavelengths is shown, including invisible ultraviolet, and visible blue, green, and yellow, and invisible infrared wavelengths in orange and red. Afterglow fades quickly in all wavelengths, except infrared. In infrared, afterglow continues to brighten until ~3 days after explosion, before beginning to fade. CREDIT: Las Campanas Observatory, Carnegie Institution of Washington (Swope + Magellan)

Afterglow faded from optical observations over days to weeks. Here, however, as observed at radio frequencies by the Very Large Array radio telescope, the electromagnetic counterpart to GW170817 is seen brightening over the first month since explosion. CREDIT: Courtesy of Gregg Hallinan, California Institute of Technology, and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory Very Large Array radio telescope

Science vs Cinema host Dr. Andy Howell explains the discovery of a never-before-seen astronomical phenomenon: a KILONOVA, the merger of two neutron stars detected via gravitational waves, which was observed by Las Cumbres Observatory.

0:00:15 Gravitational Wave Panel 0:38:20 Press Conference Q&A (Gravitational Wave Panel) 0:51:35 YouTube Q&A Session (Part 1) 1:15:20 EM Follow-up Panel 1:59:55 Press Conference Q&A (EM Follow-up Panel) 2:24:40 YouTube Q&A Session (Part 2) New details and discoveries made in the ongoing search for gravitational waves! Two panels with Q&A from the press conference hosted by the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. In between and after the two panels we did answer questions live from the YouTube chat from our YouTube Studio . It was the first time we were trying something like that ... and it did not go without some fun technical hick-ups. ^^ Find details about the new detection at Make sure to subscribe to the official LIGO Virgo YouTube Channel

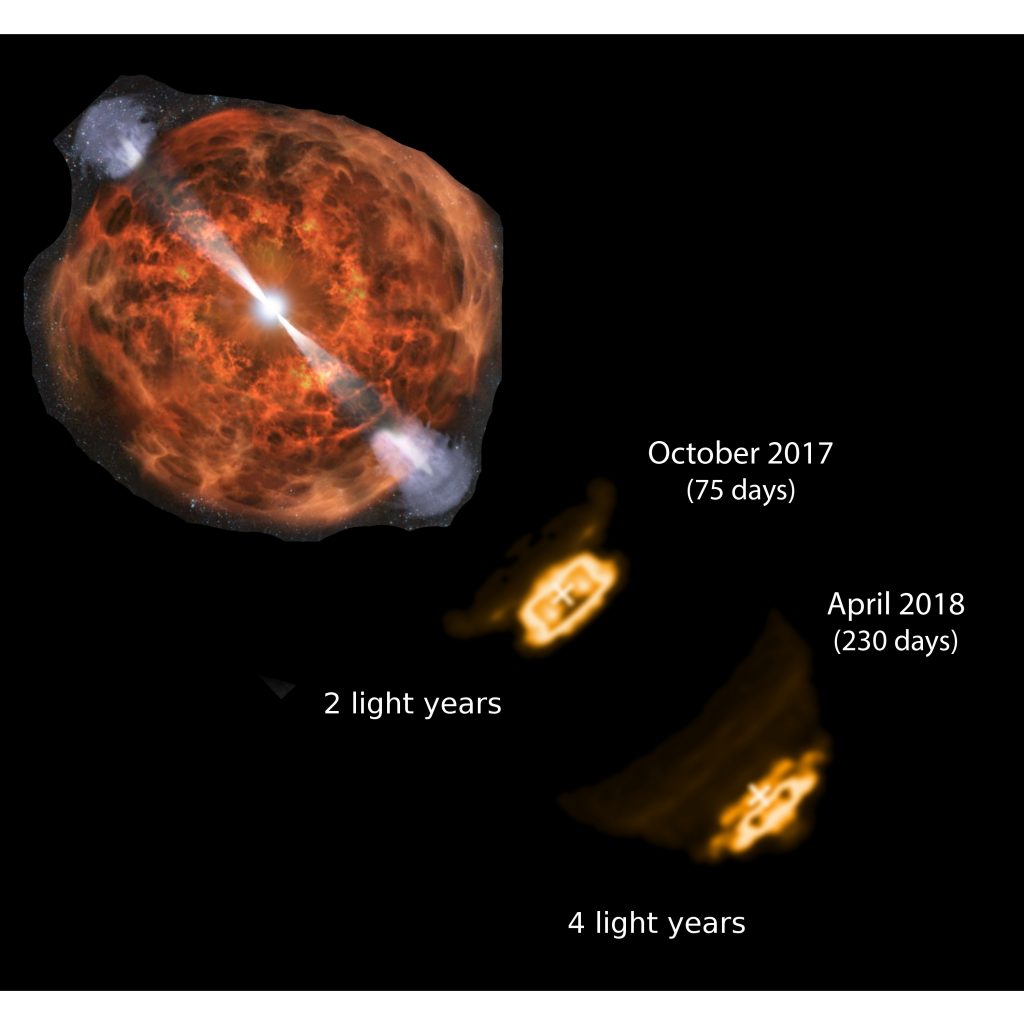

In August of 2017, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detected waves that were believed to be caused by a neutron star merger. This “kilonova” event, known as GW170817, was the first astronomical event to be detected in both gravitational and electromagnetic waves – including visible light, gamma rays, X-rays, and radio waves.

Artist’s illustration of two merging neutron stars. The narrow beams represent the gamma-ray burst while the rippling spacetime grid indicates gravitational waves. Credit: National Science Foundation/LIGO/Sonoma State University/A. Simonnet

Artist’s impression of the kilova event, with images indicating how the resulting object brightened over time. Credit: NASA/CXC/Trinity University/D. Pooley et al. Illustration: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

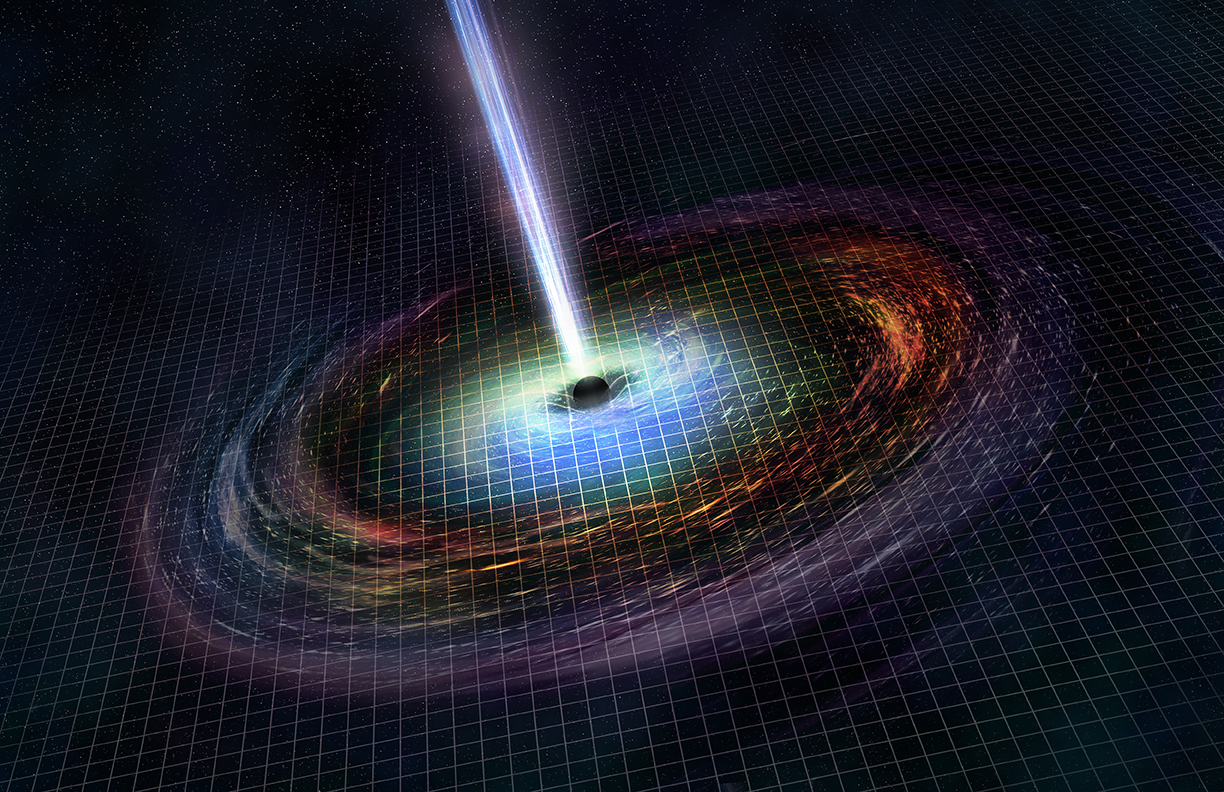

Illustration of the resulting black hole caused by GW170817. Credit: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss

See also my section on the Lisa Gravitional Observatory pathfinder:

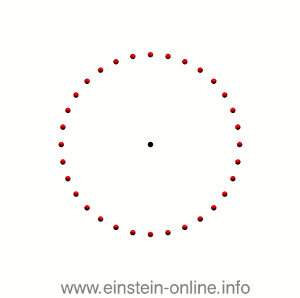

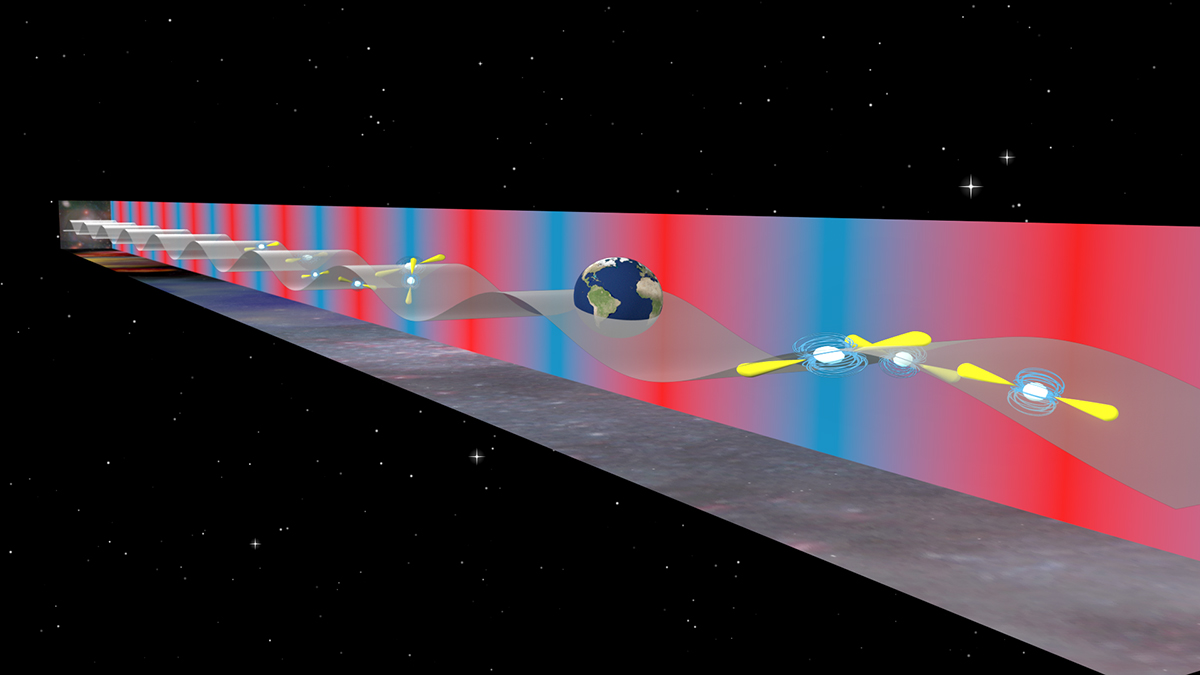

But what do gravitational waves do? For that, let us look at a simplified, entirely hypothetical situation.

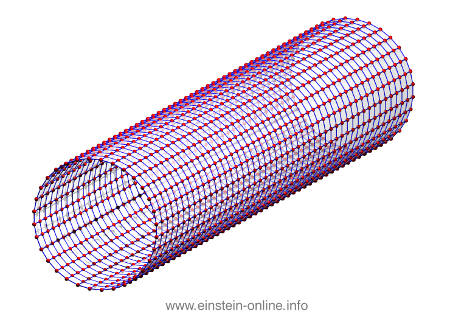

(The following are variations on images and animations originally published here on Einstein Online.)

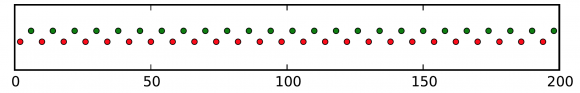

Consider particles drifting in space, far from any sources of gravity. Imagine that the particles (red)

are arranged in a circle around a center (marked in black): If a simple gravitational wave were to pass through this image, coming directly at the reader,

distances between these particles would change rhythmically as follows:

Note the distinctive pattern: When the circle is stretched in the vertical direction,

it is compressed in the horizontal direction, and vice versa. That’s typical for gravitational waves (“quadrupole distortion”). It’s important to keep in mind that this animation, and the ones that will follow,

exaggerate the gravitational wave’s effect quite considerably.

Just remember that neither the lines nor the whitish surface is physical. On the contrary,

if we want the particles to be maximally susceptible to the effect of the gravitational wave,

we should make sure they are truly floating freely, and certainly they shouldn’t be linked in any way!

As you can see, the wave is propagating through space. For instance, the point where the vertical distances

within the circle of particles is maximal is moving towards the observer. The wave nature can be seen even more clearly

if we look at this cylinder directly from the side:

As you can see, the wave is propagating through space. For instance, the point where the vertical distances

within the circle of particles is maximal is moving towards the observer.

The wave nature can be seen even more clearly if we look at this cylinder directly from the side:

The simplest situation that produces gravitational waves in the cosmos is almost ubiquitous:

two or more objects orbiting around each other under their own gravity.

The waves they generate are reminiscent to a very slow mixer in the middle of a pool of water:

This is not something you would see, of course. The wave that is pictured here represents the strength

of the minute changes in distance that would be caused by the gravitational wave, just as we’ve seen in

Gravitational waves and how they distort space.

The animation is courtesy of Sascha Husa of the Universitat de les Illes Balears.

illustration of Markarian 231, a binary black hole 1.3 billion light years from Earth.

Their collision generated the first gravitational waves we've ever detected.

Image: NASA

Nature News, March 23, 2016, doi:10.1038/531428a Source: Ref. [1]/Nik Spencer/Nature But the Event also marks the start of a long-promised era of gravitational-wave astronomy. Detailed analysis of the signal

has already yielded insights into the nature of the black holes that merged, and how they formed.

With more events such as these—the LIGO team is analysing several other candidate events captured during the detectors'

four-month run, which ended in January—researchers will be able to classify and understand the origins of black holes,

just as they are doing with stars.

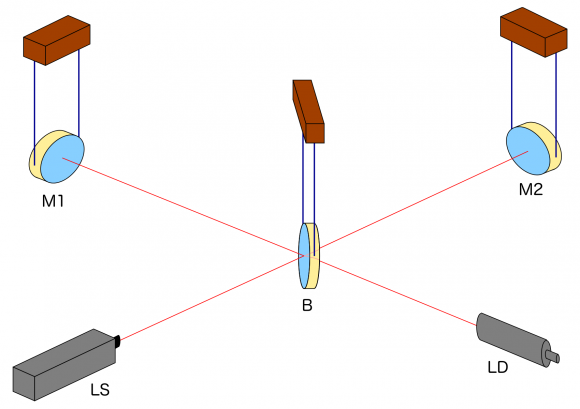

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO)facility in Livingston, Louisiana.

The other facility is located in Hanford, Washington.

Image: LIGO

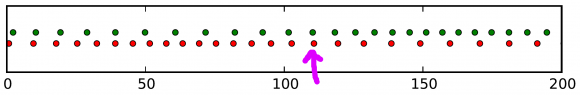

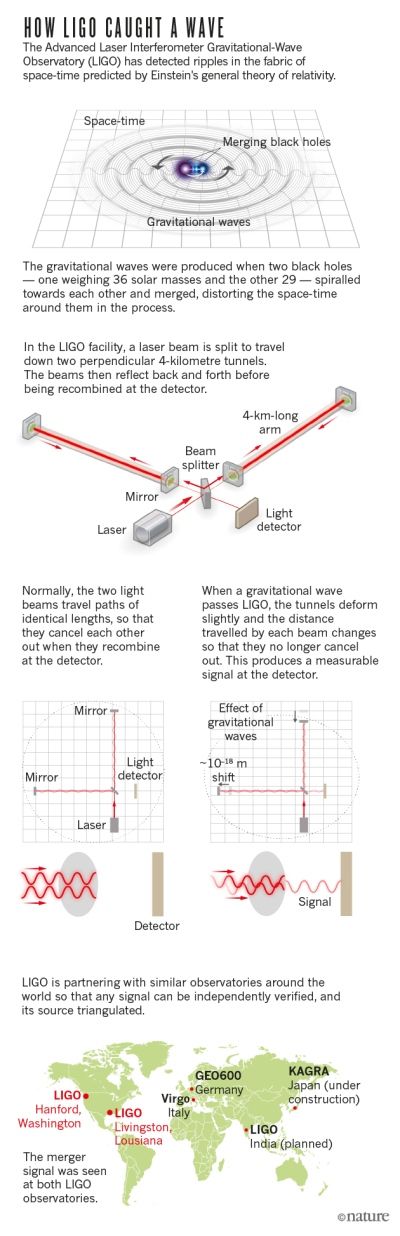

Light is sent into the detector from the (laser) light source LS to the beamsplitter B which,

true to its name, sends half of the light on to the mirror M1 and lets the other half through to the mirror M2.

At M1 and M2, respectively, the light is reflected back to the beam splitter. There, the light arriving from M1 (or M2)

is split again, with half going towards the light detector LD, the other half back in the direction of the light source LS.

We will ignore the latter half and pretend, for the sake of our simplified explanation, that all the light reaching B

from M1 or M2 goes on to the light detector LD.

Light starts at the light source to the left. Light that has left the source together, travels together

(so green and red pulses are side by side) until the beam splitter. The beam splitter then sends the green pulses on

their upward journey and lets the red pulses pass on their way towards the mirror on the right.

All the particles that arrive back at the beamsplitter after reflection at M1 or M2. At the beamsplitter,

they are directed towards the light detector at the bottom. In this setup, the horizontal arm is slightly longer than the vertical arm. Red particles have to cover some extra distance.

That is why they arrive at the detector a bit later, and we get an alternating rhythm: green, red, green, red, with equal distances in between.

This will become important later on.

Here is a diagram, a kind of registration strip, which shows the arrival times for red and green pulses at the light detector

(time is measured in “animation frames”): The pattern is clear: red and green pulses arrive evenly spaced, one after the other.

Next, let’s switch on our standard gravitational wave (exaggerated, passing through the screen towards you, and so on). Here is the result: We have trained our camera on the beamsplitter (so in our image, the beamsplitter doesn’t move). We ignore any slight changes in distance

between beamsplitter and light source/light detector. Instead, we focus on the mirrors M1 and M2, which change their distance from the beamsplitter

just as we would expect from the earlier animations.

Look at the way the pulses arrive at our light detector: sometimes red and green are almost evenly spaced,

sometimes they close together. That is caused by the gravitational wave. Without the wave, we had strict regularity.

To spot gravitational waves directly for the first time ever, scientists had to measure a

distance change 1,000 times smaller than the width of a proton.

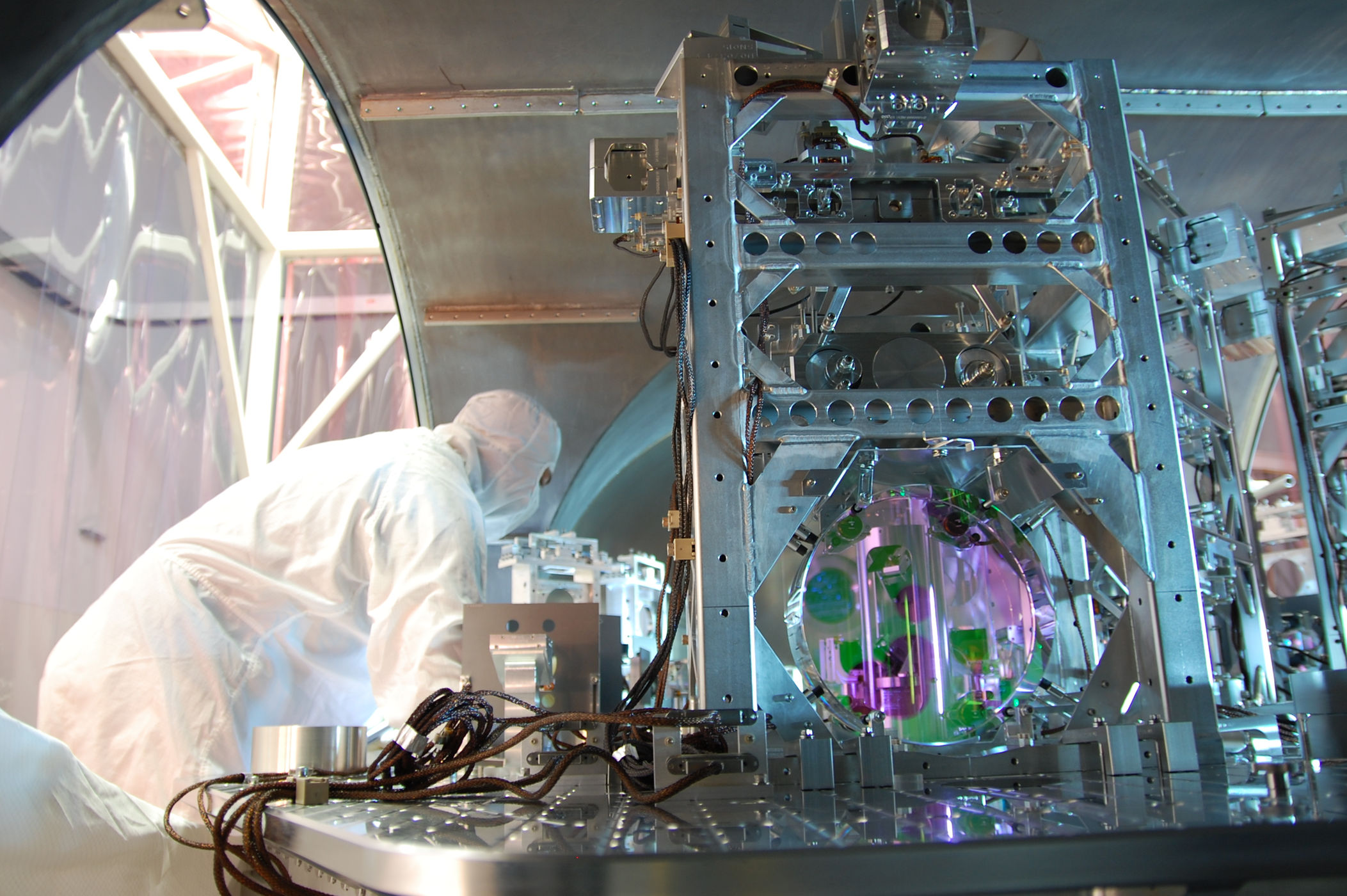

Published on Feb 11, 2016 After a decades-long quest, The MIT-Caltech collaboration LIGO Laboratories has detected gravitational waves,

opening a new era in our exploration of the universe. Read more: https://news.mit.edu/2016/ligo-first-d... Produced by MIT Video Productions and MIT News Office Producer/Editor: Bill Lattanzi Footage courtesy of: Hans Peter Bischof; California Institute of Technology; Jet Propulsion Laboratory; LIGO,

A Passion for Understanding, by Kai Staats; MIT; National Science Foundation; Roger Smith; Virginia Trimble, widow of

Joseph Weber; Wikipedia Commons Category Science & Technology License Standard YouTube License

An artist's impression of a Gamma Ray Burst. Credit: Stanford.edu

Published on Jun 14, 2016 In 2015 scientists working at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave observatory, or LIGO,

detected gravitational waves for the first time. But how did they do it? What is a gravitational wave?

And why is confirming something that Albert Einstein predicted a hundred years ago one of the greatest

scientific achievements of the past century? HUGE Thanks to the LIGO team and the National Science Foundation for funding amazing projects like LIGO The University of Chicago LIGO group is comprised of Daniel Holz, Ben Farr, Hsin-Yu Chen, and Zoheyr Doctor, and they all contributed to the results described in this video. ►Subscribe: ►Let us know what you think of our show! The Good stuff patreon ►Follow us on Twitter: ►Follow us on instagram: goodstuffshow ►Like us on facebook Digital street team: Sign up for our mailing list: The Good Stuff is a proud member of the PBS Digital Studios family

By Calla Cofield, Space.com Staff Writer | August 1, 2016 07:36am ET

<>

A reading of the article “Gravitational Waves” by Wal Thornhill. Narrated by David Harrison, proprietor of Stickman On Stone. The headline shrieked, “Gravitational waves have been discovered; Einstein proved right again after 100 years.” This milestone from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) was announced in February 2016. Two weeks later, Wal posted his critical analysis. Some incredibly detailed claims were made; the signal originated in the last fraction of a second before the fusion of two black holes somewhere in the southern sky, it was based on computer modeling that these black holes had joined 1.3 billion years ago, and they had a combined mass 29-to-36 times greater than the Sun. A mathematical computer model is not real evidence for those claims. The public is being baffled by punctilious abstractions. This isn’t science. Black holes are a flawed theoretical concept used to make the minuscule force of gravity responsible for the most energetic compact bursts of energy in the universe. However, what can succeed without stretching either space-time or credulity, is the most concentrated form of stored electromagnetic energy known to science—a plasmoid. In summary, the results of the LIGO experiment have nothing to do with imagined Gravitational Waves. SOURCE ARTICLE Holoscience: EU Views - February 25, 2016 Ideas and/or concepts presented in this program do not necessarily express or represent the Electric Universe model or the views of The Thunderbolts Project or T-Bolts Group Inc. If you see a CC with this video, it means that subtitles are available. To find out which ones, click on the Gear Icon in the lower right area of the video box and click on “subtitles” in the drop-down box. Then click on the subtitle that you would like. Become a Producer through the PATREON Rewards program... Subscribe to Thunderbolts eNewsletter Guides to the Electric Universe Electric Universe Books & Merch Electric Universe Books & Merch Electric Universe by Wal Thornhill Facebook Twitter @tboltsproject The Thunderbolts Project™ Trademark of T-Bolts Group Inc. a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization. Copyright © 2016–2024 T-Bolts Group Inc. & Holoscience.com. All rights reserved.

In 1915, Einstein put the finishing touches on his Theory of General Relativity (GR), a revolutionary new hypothesis that described gravity as a geometric property of space and time. This theory remains the accepted description of gravitation in modern physics and predicts that massive objects (like galaxies and galaxy clusters) bend the very fabric of spacetime.

12 Einstein crosses discovered using data from the Gaia DR2. Credit: The GraL Collaboration

Gaia mapping the stars of the Milky Way. Credit: ESA/ATG medialab; background: ESO/S. Brunier

Using the gravitational lensing technique, a team was able to examine how light from distant quasar was affected by intervening small clumps of dark matter. Credit: NASA/ESA/D. Player (STScI)

Swirling around the dark mass beneath them, this moving animation

shows how scientists used the stars to identify an enormous black hole at the centre of our galaxy.

Researchers monitored the orbit of the stars circling the centre of the Milky Way

to map out the size of the phenomenon, which is four million times heavier than the sun.

Over 16 years they tracked 28 stars and determined the black hole, known as Sagittarius A*,

was influencing their movements.

Read more:

Credit:

ESO/ S. Gillessen, R. Genzel

In a 16-year long study, using several of ESO's flagship telescopes, a team of German astronomers has produced

Credit:

ESO/ S. Gillessen, R. Genzel

source:

Tracking Stars Orbiting the Milky Way's Central Black Hole

the most detailed view ever of the surroundings of the monster lurking at our Galaxy's heart —

a supermassive black hole. The research has unravelled the hidden secrets of this tumultuous region

by mapping the orbits of almost 30 stars, a five-fold increase over previous studies.

One of the stars has now completed a full orbit around the black hole.

Enormous Structures Might be Hiding in the Center of our Galaxy

Astronomers Get as Close as They Can to Seeing the Black Hole at the Heart of the Milky Way

Since the 1970s, astronomers have theorized that at the center of our galaxy, about 26,000 light-years from Earth, there exists a supermassive black hole (SMBH) known as Sagittarius A*. Measuring an estimated 44 million km (27.3 million mi) in diameter and weighing in at roughly 4 million Solar masses, this black hole is believed to have had a profound influence on the formation and evolution of our galaxy.

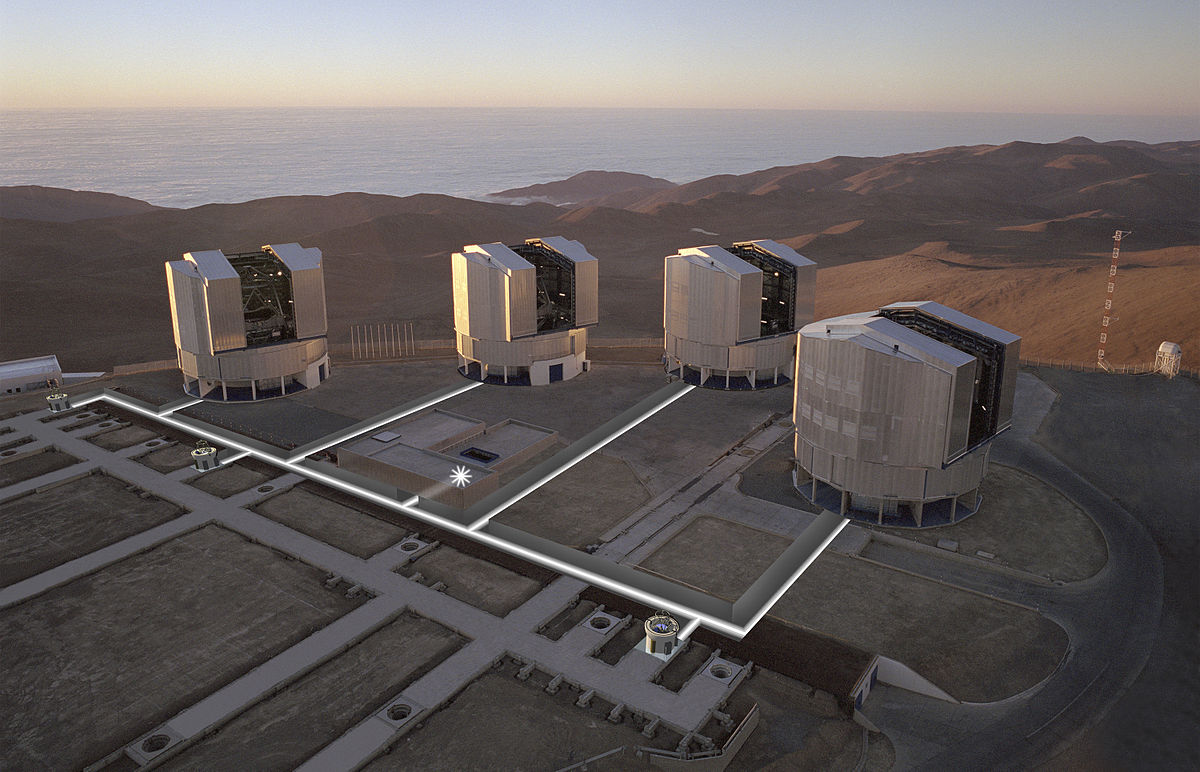

The four Unit Telescopes that make up the ESO’s Very Large Telescope, at the Paranal Observatory. Credit: ESO/H.H.Heyer

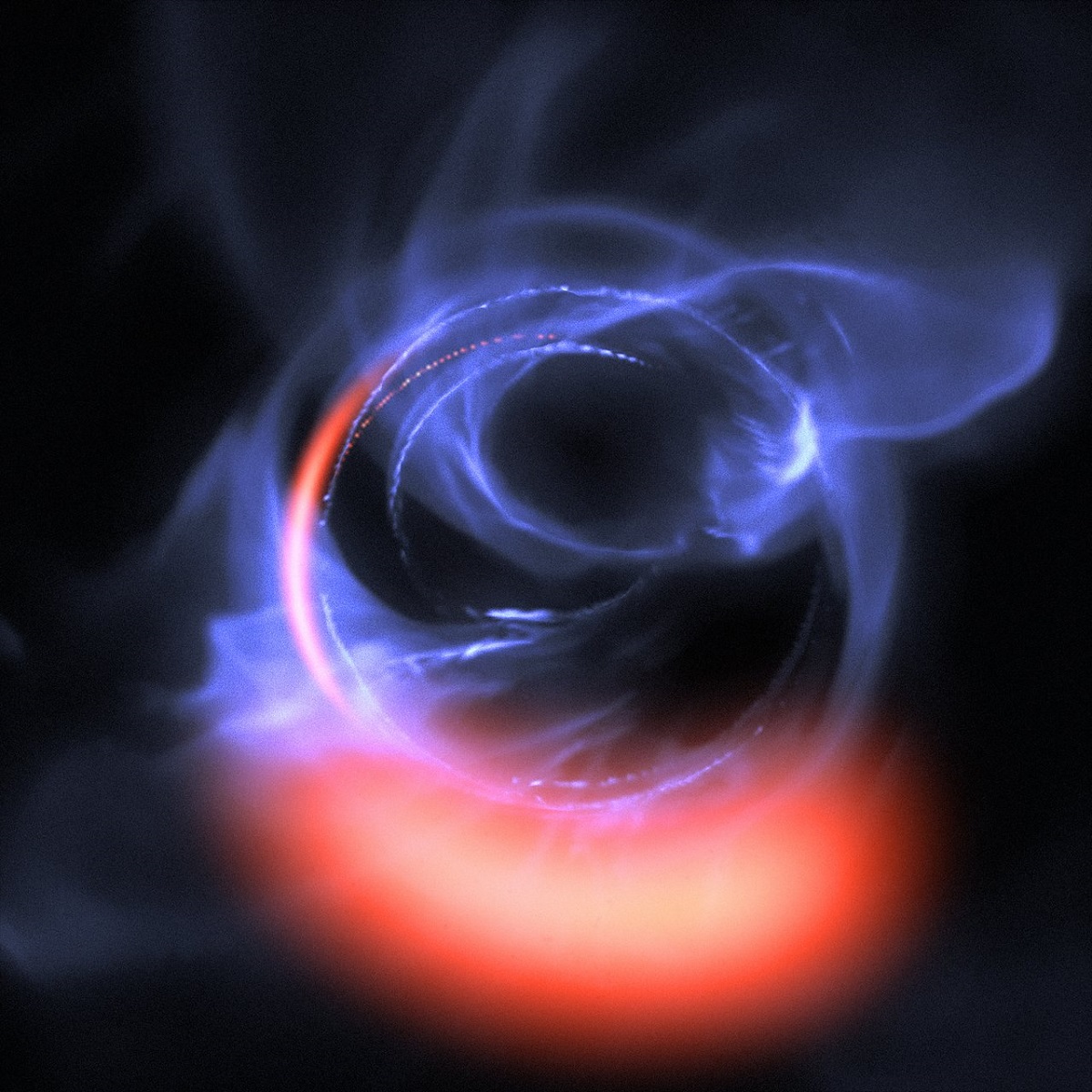

ESO’s exquisitely sensitive GRAVITY instrument has added further evidence to the long-standing assumption that a supermassive black hole lurks in the centre of the Milky Way. New observations show clumps of gas swirling around at about 30% of the speed of light on a circular orbit just outside a four million solar mass black hole — the first time material has been observed orbiting close to the point of no return, and the most detailed observations yet of material orbiting this close to a black hole. This visualization uses data from simulations of orbital motions of gas swirling around at about 30% of the speed of light on a circular orbit around the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A*. More information and download options:

ESO’s exquisitely sensitive GRAVITY instrument has added further evidence to the long-standing assumption that a supermassive black hole lurks in the centre of the Milky Way. New observations show clumps of gas swirling around at about 30% of the speed of light on a circular orbit just outside a four million solar mass black hole — the first time material has been observed orbiting close to the point of no return, and the most detailed observations yet of material orbiting this close to a black hole. The video is available in 4K UHD. The ESOcast Light is a series of short videos bringing you the wonders of the Universe in bite-sized pieces. The ESOcast Light episodes will not be replacing the standard, longer ESOcasts, but complement them with current astronomy news and images in ESO press releases. More information and download options: Subscribe to ESOcast in iTunes! Receive future episodes on YouTube by pressing the Subscribe button above or follow us on Vimeo: Watch more ESOcast episodes: Find out how to view and contribute subtitles for the ESOcast in multiple languages, or :translate this video on YouTube Credit: ESO Directed by: Nico Bartmann. Editing: Nico Bartmann. Web and technical support: Mathias André and Raquel Yumi Shida. Written by: Sara Rigby and Calum Turner. Music: written and performed by STAN DART (www.stan-dart.com). Footage and photos: ESO/Gravity Consortium/L. Calçada/M. Kornmesser/N. Risinger (skysurvey.org) Executive producer: Lars Lindberg Christensen. Caption author (Arabic) Shimaa Alaa Caption author (Portuguese (Brazil)) Caroline M. Caption author (Romanian) Elena C. Robe Caption author (Polish) Tomasz Kozłowski Caption author (Portuguese) Caroline M. Caption author (Vietnamese) Sang Mai Thanh Caption author (Italian) Andrea Mazzilli Category Science & Technology License Creative Commons Attribution license (reuse allowed)

Infographic on the binary binary black hole merger that produced the GW231123 signal. Credit: Simona J. Miller/Caltech

Published on Jun 8, 2015 When massive objects crash into each other, there should be a release of gravitational waves. So what are these things and how can we detect them? Support us More stories at: Follow us on Twitter: @universetoday Follow us on Tumblr Like us on Facebook Google+ - Instagram - Created by: Fraser Cain and Jason Harmer Edited by: Chad Weber Music: Left Spine Down - “X-Ray” Who wants to bet against Einstein? You? You? What about you?

How interferometers measure ripples in spacetime to detect Gravitation Waves. Credit: ©Johan Jarnestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.